We’ve all heard a common complaint among adults about learning a language that goes something like this: “I wish I had started to learn this language as a child. Kids learn languages so much easier.”

Since this belief is so pervasive, it must be true, right? Turns out it’s actually wrong.

While children do have certain advantages when learning a second language, like being more adept at speaking without a foreign accent, they don’t have it inherently easier. In fact, some studies actually suggest that you may be better off learning as an adult.

After all, some people are able to become fluent in just three months. It usually takes kids until they are 5 or 6 before they are truly speaking their first language fluently!

So, why does it seem easier for a child to learn a second language? How much of this language learning myth is true? Below we outline a couple ways that kids and adults differ in learning languages and how that affects each one's ability to learn efficiently.

[See also: Our complete toolkit for How to learn a language on your own]

Truth or myth: do kids learn languages more easily?

Kids learn languages differently, NOT more easily

Children seem to learn a second language easier than adults. After all, they pick up words, phrases, and grammar seemingly without much effort.

And this seems well-supported by science: in a study conducted by Dr. Paul Thompson at UCLA, researchers established that kids use a part of their brains called the “deep motor area” to acquire new languages. This is the same brain area that controls unconscious actions like tying a shoe or signing your name. Thompson and colleagues concluded that language acquisition is second nature to children, thus leading many to believe it would be fruitless to attempt language learning after the brain rewires the way it acquires new languages.

Unfortunately, this oversimplification misses an important caveat: adults are great at conscious learning. As we get older, our brain becomes more and more skilled at complex thought, and our capacity for intellectual learning grows. Adults may need to consider grammar points and learn the rules in a more direct way to learn them well, but this actually helps second language learning in many cases.

After all, adults are much more likely to be attempting to take on a new language in the classroom than running around with native speakers. Although language learning becomes an academic endeavor in adulthood, it is one we are prepared to master well.

And there's lots of evidence we're successful at this. In a study by MIT, researchers found that there are lots of adults that learn a language and get to native-like fluency.

Kids are more open to making mistakes

Unfortunately, fewer mistakes doesn’t mean no mistakes, which is where many adults get hung up while learning a new language. Not only have adults developed a greater ability to learn complex ideas, but they have also developed an adverse attitude towards errors.

Adults are more likely to feel embarrassed by minor mistakes than children. (This is the same reason many people speak a foreign language better when drunk.) Our affective filters can lead to adults either giving up more easily or fearing mistakes so much that it delays development in speaking abilities.

Due to the higher inhibitions that come with age, especially in professional settings, adults can self-sabotage learning efforts. Learning from mistakes is a key way that we retain information, and by avoiding mistakes, adults retard that process.

Unfortunately, adults’ learning efforts can be similarly sabotaged by other adults. Few adults feel any hesitation in correcting a child’s language mistakes. After all, that’s something we would feel comfortable doing for children even in their first language. Not all adults, though, feel it is their place to correct the mistakes of a colleague or an acquaintance. When these errors go unnoticed, they become “fossilized” in memory and can be very difficult to fix later.

The preexisting language knowledge of adults helps

Adults’ past experiences and studies in a first language prime them to learn a second language more easily. Children are still trying to master their first language, while adults have an advanced understanding of the mechanics of the grammar, spelling, and punctuation in that first language. This means that adults instinctively understand what is required to build a sentence and other vital language concepts, such as parts of speech.

This knowledge transfers to a second language, allowing adults to pick up the mechanics of a new language more quickly—even if they differ from the mechanics of the native language. This is because adults have developed the skills to better find patterns and apply them. This gives adults a significant advantage in deducing and applying language rules, leading to fewer mistakes along the way. The mastery of their mother tongue helps adults to learn a second language.

Adults have different language expectations

Still, even when mistakes are addressed as judiciously in adult speech as in children’s, we tend to place less importance on mistakes made by children when assessing overall fluency. Children are only expected to be able to communicate at the same level expected of a native speaker that age. This generally makes standard of fluency for children lower, especially in younger children. A seven-year-old who is “fluent” probably has much less sophisticated grammar and vocabulary in a second language than an adult with basic communication-level language skills and several months of studies under her belt.

The standards are simply different.

In any setting, children use smaller vocabularies and simpler syntax than adults. Adult communication is much more complicated. Adults (and even teens) must be able to speak more in-depth about a broader range of topics than children would be expected to do. They must also be able to adjust language to the appropriate setting, meaning that fluent adults must know slang, workplace lingo, and other specialized speech that would be mostly irrelevant to a child. While it may seem like young children become fluent almost immediately, it bears keeping in mind the differences in what “fluent” speech means in different contexts.

Is there a cut-off date for language learning?

The answer is definitely: no. You're never too old to learn a new language.

Adults have as much capacity as kids to learn another language. The process and expectations simply differ. The implicit learning of childhood may change as we age, but our abilities to pick up the mechanics of a new language and infer the patterns and meanings of unfamiliar languages never fully go away. In fact, some studies now even indicate that adults are actually better at learning new elements of languages implicitly overall.

For example, one study found that when older and younger participants were exposed to the same amount of foreign language instruction, the older group learned better than the younger group.

[See also: How long should it take to learn a language?]

Since it turns out there isn’t much truth at all to the myth that kids learn languages easier, you now have no excuse not to go out and learn a new language today. And there are many reasons why adults want to learn foreign languages: to gain an advantage in an international workplace, converse with the family of a foreign partner, travel the world and be able to learn the culture by communicating with locals ... the list could go on.

Learning a language isn't easy—but you can do it

Although adults can learn languages, no one said it would be easy. It takes motivation, time, and an insane amount of practice. Where do you even start teaching yourself a language without the help of you 5th grade Spanish teacher? With language resources like Brainscape that are specially customized for the way adult brains work, you will be more likely to succeed.

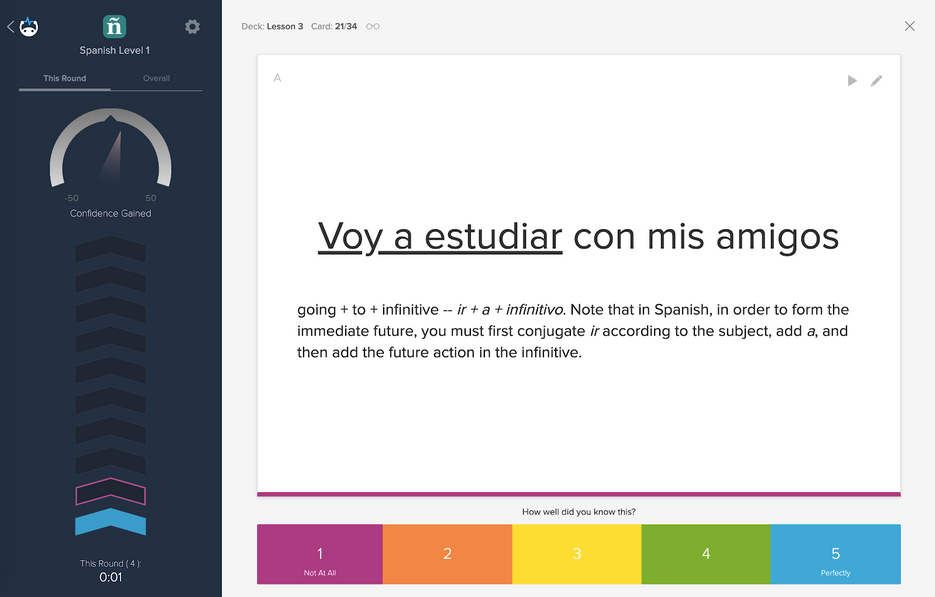

The team at Brainscape spent years working with experts to develop a foreign language curriculum for our web and mobile flashcard app. We've created an optimized technique for learning a foreign language using cognitive science with successful curricula for learning Spanish and learning French.

Not only that, but we have ALSO developed a complete toolkit to learn a foreign language online.

If you dedicate yourself to the process, you can trust Brainscape to help you learn a new language at any age. So, dive into out free toolkit and start learning a foreign language today!

Sources

Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Pinker, S. (2018). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition, 177, 263-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.007

Muñoz, C. (Ed.). (2006). Age and the rate of foreign language learning (Vol. 19). Multilingual Matters.

Thompson, P. M., Giedd, J. N., Woods, R. P., MacDonald, D., Evans, A. C., & Toga, A. W. (2000). Growth patterns in the developing brain detected by using continuum mechanical tensor maps. Nature, 404(6774), 190-193. https://doi.org/10.1038/35004593