“You have not taught until they have learned” ― John Wooden

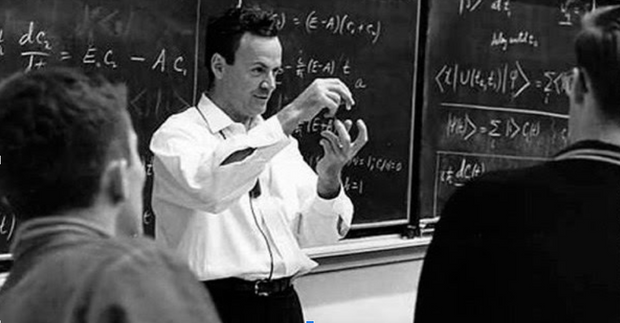

The year is 1962 and the place is the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). There’s a lecture on physics in progress. At the front of the hall, scratching away on a huge blackboard is Nobel laureate, Richard Feynman.

There’s more than a whiff of cigarette smoke in the air, and students are busily writing away in notebooks, slide rulers at the ready. It’s one of the famous Feynman Lectures, where Feynman, “the Great Explainer”, would break down advanced physics concepts into their most basic elements so they could be grasped by the first-year students.

This was ground zero for the popularization of the Feynman Technique, a ground-breaking way of learning that’s now used by top students everywhere. Add the Feynman Technique to your toolkit of effective study methods and optimize your learning.

In this article, we’ll explore how you can use the Feynman Technique to grasp new concepts with the same ferocious iron grip a toddler uses to seize a gummy bear.

What is the Feynman Technique?

In its simplest form, this technique involves you, the learner, figuring out how to teach a complex concept you’ve just learned to a complete newbie.

At a deeper level, practicing this means you have to remove all the assumptions propping up your knowledge on a subject. It will take your understanding back to its most basic framework, and this has real advantages.

When you build from solid bedrock, you can master complex subjects, not only with greater confidence but with greater efficiency too. The Feynman Technique is particularly useful for scientific and mathematical concepts. Each successive step is perched upon the shoulders of slightly more elementary theorems and lessons.

In other words, mastering the complex requires you to perfect the simple.

The Feynman Technique is also useful for learning aspects of history, literature, and subjects with complex theories (like economics). Any subject that has a framework of information that builds upon itself can be picked apart and better understood using this approach.

Why the Feynman Technique works

Using this technique can truly solidify your intimate understanding of a subject. It’s essentially the difference between someone who thinks they know how a car works because they’ve driven one, and someone who’s taken a car engine apart, and put it back together again.

The first person thinks they know, while the second person really knows. And which person would you rather have with you when your car breaks down on a dark and stormy night?

When you’re studying for a test, you may be neck deep in notes, flashcards, caffeine, and sugar. You may also feel that cracking open one more textbook will send you into a study-induced Netflix binge. This is when you should lay aside all your study materials, go outside, and use the Feynman Technique.

The primary principle of the Feynman Technique is simple: the way to test your understanding of a concept is to teach what you’ve learned to someone with no background in the field. Ideally, a child.

It’s impossible to successfully teach a complex topic to a six year old without fully understanding it yourself.

Children have short attention spans, so long-winded, rambling explanations will get you nowhere. They also have the uncomfortable habit of asking “But why?” until you’re ready to scream.

Annoying as it can be, this curiosity about why things are the way they are isn’t just shared by children everywhere. It’s also shared by great scientists.

“If you can't explain it to a six year old, you don't understand it yourself.” ― Albert Einstein

According to Richard Feynman, this technique of understanding from first principles was the key to his considerable success.

He began developing his technique when he was a student at Princeton. He had a “Notebook of Things I Don’t Know About.” He would use this notebook to boil knowledge down to its essentials, removing everything that was extraneous, or expressed in technical jargon.

Then Feynman connected the things he knew about to the things he didn’t. Doing this helped him uncover assumed knowledge, and made knowledge gaps crystal clear.

We now know that the technique of simplifying material for teaching is so useful for learning because it invokes a mental process known as metacognition, or "thinking about your thinking". This act of self-reflection is critical to how Brainscape itself helps you improve your knowledge retention so much.

Reducing a subject to its first principles

“Knowing the name of something does not mean you truly understood it.” ― Richard Feynman

The first step in using this technique is to go back to basics. Like Greek philosopher Socrates, Feynman realized that knowing the name of something did not mean you truly understood it.

Jargon can cover up your assumptions, especially ones that are built over knowledge gaps or plain ignorance. Leaving technical jargon unexamined means you might be building a knowledge structure with a shaky foundation.

Feynman discovered how widespread this problem was when he started teaching his kids physics using their first-grade science book.

“It began with pictures of a mechanical wind-up dog, a real dog, and a motorcycle, and for each the same question: “What makes it move?”

The proposed answer—“Energy makes it move”— enraged him ... To tell a first-grader that “energy makes it move” would be no more helpful, he said, than saying “God makes it move” or “moveability makes it move.”

— James Gleick, from: Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman

So, one of the key challenges in the Feynman Technique is to remove all technical jargon from your explanations.

Following this method means you would be able to explain to a child how a mechanical wind-up dog moves, without using the word ‘energy.’

To do this you’d have to truly understand what energy is, how it functions, and what its effects are. You’d need to be able to describe concepts like stored force, mechanical energy, torque, and motion in simple, non-technical terms.

For example: when you turn the key to wind up a toy dog, you’re winding the steel spring tight inside the toy, forcing it to fit into a smaller space. The tiny parts of that steel spring want to return back to their original shape, but they can’t because the key is holding the spring in place. When you release the key, the spring pushes against the cogs inside the dog. The cogs move. Because the cogs are attached to the dog’s legs, these also move, and the toy dog walks around.

Explaining things using this simple vocabulary means you cut out assumptions. Plain English means you can’t use words that stand for concepts, or words that replace a group of other facts.

Using the Feynman Technique for studying means you’ll build the kind of solid understanding that w on’t dissolve in a cloud of caffeine fueled stress on exam day. Deconstructing and rebuilding your knowledge also means you’ll be able to rapidly progress into advanced fields of science or maths.

Practicing the Feynman Technique while studying

Here’s how you can practice the Feynman Technique as part of your exam study habits:

1. Set the stage

Before you wrap up your studying for the day, do a quick scan of your notes or Brainscape flashcards to identify the area in which you have the lowest confidence. Keep this at the top of your mind for the next time you're out and about.

2. Take a walk

Next time you're in a setting where you couldn't otherwise be studying (e.g. when you're jogging, walking, showering, driving, etc.), recite a sample "lecture" you might teach about each of those topics.

For example, “Gravity, or gravitation, is a natural phenomenon by which all things with mass or energy—including planets, stars, galaxies, and even light—are attracted to one another.”

3. Become your very own annoying first-grader

Now that you have your topic definition, pretend you don’t know the first thing about physics and annoy the crap out of yourself. Every time you state something, ask yourself: why? Your goal is to dig deep and uncover the assumptions that are propping up your knowledge.

For example:

You: “Gravity makes objects fall to the ground.”

You as a first-grader: “Why?”

You: “Because a force of attraction exists between the Earth and every object on it.”

You as a first-grader: “Why?”

You: “Because anything that has mass (weight) is attracted to other things with mass, even these two pencils here. But these pencils are so tiny compared to earth that you can't see them getting attracted to each other."

And so on.

Ideally, this conversation would dive deeper and deeper into the elementary framework of the Laws of Gravitation until even that first-grader is able to grasp these laws of physics. At least to the extent that you need to know for your test.

4. Keep your explanation short

Think about how long a six year old can focus on anything that’s not Spongebob Squarepants. A short explanation means you know what’s important, and what’s peripheral. A few well-crafted sentences should suffice for even the most complex of topics.

5. Tell a story

Transform your knowledge into a story. For example, in trying to remember an historical event, rather than just parrot-fashion learning a suite of dates and facts, recount the event as an engaging story. Humans are narrative creatures and we are far more likely to remember facts if they’re woven into a story.

6. Encourage curiosity

All his life, Feynman retained a sense of wonder at the beauty of the world, its mystery, and how it was all put together. Staying curious means you’ll never be satisfied with an inch-thick explanation for why things are the way they are.

Curiosity compels you to dive deep into your field and get to the heart of things. This need to discover the unknown has driven more human achievement than anything else, and it’s the true essence of the Feynman Technique.

7. Go forth and actually teach

Your ability to teach the knowledge you have learned is the true test of just how well you have learned it. Bribe some unsuspecting six year old (or your dog) to listen to you explain what you’ve been learning. You’ll need to make your explanation interesting and be ready to answer some left-field (potentially thought-provoking) questions! Kids say the darndest things.

Quite apart from the benefit to you, this teaching can be its own reward. When you get it right, there’s this moment when the person you’re teaching grasps the concept for the first time. And the look on their face as a piece of the world clicks into place for them is pure magic.

When you are able to elicit this response from your young student, you’ll know you’ve truly mastered your subject.

8. Revise and refine

Once you're back in front of a computer or smartphone, go back into Brainscape and downgrade the confidence levels of the digital flashcards you weren't able to recite well, so that they show up again soon in your ongoing study stream.

(Or if you don't yet have flashcards in Brainscape, make your own flashcards or have a classmate make flashcards for you.)

9. Rinse and repeat

Repeat this cycle for the final hours or days before your exam, until your lectures are better than your instructor's!

The Feynman Technique: break down concepts and build them back up

In summary, the Feynman Technique is a way to break down concepts to their most basic elements, then put them back together again. Following this method allows you to deeply internalize complex topics and build a rock-solid foundation for new information.

You’ll know you’ve truly mastered this when you’re able to teach a complex concept so even a child can understand it.

This will not just help you ace your exams. It's also a great skill for life. The best entrepreneurs, salespeople, doctors, lawyers, and teachers are able to take complex information and distill it into a simple message that’s easily understood. These talented storytellers end up running the world.

Try it yourself!