I had always thought of myself as a morning person. When I got to college, I made sure to schedule all my classes so that they started as early as possible and finished by about 3 in the afternoon.

If you can relate, you can imagine how annoyed I was when my schedule one semester worked out so that none of my classes started until 2:30 at the earliest. How was I going to get through the day when I was sure that I would be falling asleep during all my classes?

But guess what: As my daily class schedule adjusted to later in the day, so did my sleep schedule. I started sleeping until 9 or 10 am, shifting my "morning" routine a bit later, and being able to pay attention in my afternoon classes without any urge to sleep.

It also came as a complete surprise when I found that my grades were better during my PM-focused semester than they had ever been previously. What did this mean, aside from the fact that clearly I had been mistaken in thinking that I was hopelessly and permanently a morning person?

We all know someone who’s chipper at 6 am and already solving world peace before breakfast. And we all know someone else who doesn’t reach peak productivity until the moon is high and the house is silent. So, who’s the better learner—the lark or the night owl?

You Do You: Learning Is Personal

Studies show that people generally learn best at times that align with their natural circadian preferences. Morning people tend to thrive early in the day, while night owls hit their stride later on. Your internal clock has a lot to say about your ability to concentrate, recall information, and stay alert during a study session.

So, if you find that you're way sharper in the evenings or surprisingly productive before sunrise, trust that instinct—it’s backed by science.

Night Owls, Rejoice: Late-Night Studying Can Boost Memory

Here’s a fun twist: research suggests that reviewing material right before bed may actually help it stick better. That’s because as you sleep, your brain gets busy moving fresh knowledge from short-term memory into long-term storage—a process known as declarative memory consolidation.

In other words, your pre-bedtime study session might be doing more work after you’ve closed the books.

Sleep = Study Power

That said, don’t sacrifice sleep to squeeze in study time. Without enough rest, your ability to focus, remember, and regulate emotions takes a nosedive. REM sleep—the phase where your brain locks in long-term memories—is especially important. And if you cut the night short (say, after a late-night cram session), you risk undoing all that hard work.

Moral of the story: quality sleep isn’t a luxury—it’s an essential part of the learning process.

Brainscape Can Help Anytime, Anywhere

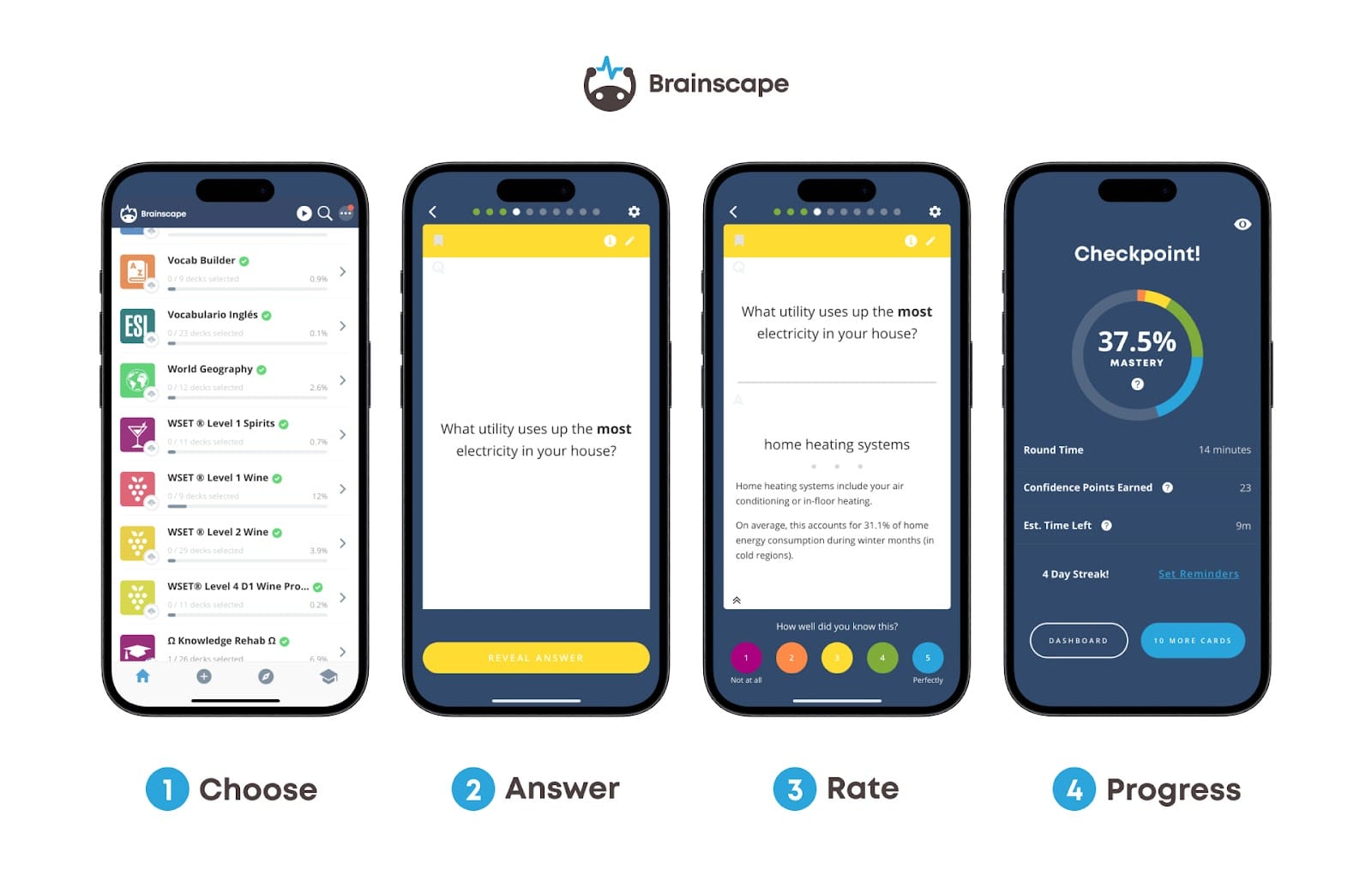

Whether you’re a 6am flashcard warrior or a midnight study ninja, Brainscape has your back. Our adaptive flashcard app uses spaced repetition and confidence-based learning to help you study smarter, not longer—whenever your brain is at its best.

You can create your own flashcards or tap into our library of expert-certified content across a massive range of subjects. And with mobile and desktop access, it’s easy to sneak in study time at your peak—or during those random five-minute windows in your day.

FAQ: What's the Best Time of Day to Study for Optimal Learning?

What is the best time of day to study?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. It depends on your personal circadian rhythm. Some learners are most alert and focused in the early morning, while others do their best work in the afternoon or evening. The key is to study during the time of day when you feel most energized and mentally sharp.

What is the optimal study time per day?

The optimal amount varies by person and context, but quality is more important than quantity. Aim for focused, distraction-free sessions with breaks, and use techniques like spaced repetition to make even short study periods more effective.

What are the best hours of the day to learn?

Your “best hours” are whenever you feel naturally focused and alert. This often means mid-morning for early risers and late evening for night owls. Just be sure to prioritize sleep, as rest plays a vital role in consolidating what you’ve studied.

Final Thoughts: Timing is Everything (But Not the Only Thing)

Yes, the time of day can absolutely affect your ability to learn. But that’s not the whole story. Your energy levels, sleep habits, study tools, and overall self-awareness matter just as much—if not more. The key is to pay attention to your body’s natural rhythm and work with it, not against it.

So whether you’re sipping coffee with the sunrise or powering through flashcards by lamplight, make sure you’re studying smart, staying well-rested, and using tools like Brainscape to make the most of your effort. Your brain—and your grades—will thank you.

Additional Reading

- Can you learn while sleeping? The relationship between studying and sleep

- Is waking up early bullsh*t?

- How to create a study routine that maximizes productivity

Sources

Adan, A., Archer, S. N., Hidalgo, M. P., Di Milia, L., Natale, V., & Randler, C. (2012). Circadian typology: A comprehensive review. Chronobiology International, 29(9), 1153-1175. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.719971

Bhatti, U., Ahmadani, R., & Chohan, M. N. (2017). Intelligent Quotient (IQ) Comparison between Night Owls and Morning Larks Chronotypes in Medical Students. National Editorial Advisory Board, 28(11), 29-31.

Beşoluk, Ş., Önder, İ., & Deveci, İ. (2011). Morningness-eveningness preferences and academic achievement of university students. Chronobiology International, 28(2), 118-125. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2010.540729

Cavallera, G. M. & Giudici, S. (2008). Morningness and eveningness personality: A survey in literature from 1995 up till 2006. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.009

Holloway, J. (1999). Giving our students the time of day. Educational leadership, 57(1), 87-88.