Many people have heard the story of how I created the original Brainscape prototype in an Excel macro while working in Panama with the World Bank.

They also know how I became so obsessed with that personal learning project that I ultimately pivoted my career and earned a master’s degree in Education Technology at Columbia University, using Brainscape as my capstone project.

What most people don’t know are the details of that project, and the results that convinced me to put up my life savings to build a flashcard app capable of leveraging the cognitive science of learning.

So in this article, I've published those details: the experiment that validated my passion and ultimately led to the study tool that 10 million+ students use today.

Background: How Did Brainscape Start as a Master’s Thesis?

The Academic Setup

In 2007–2008, I was enrolled in the Education Technology master’s program at Columbia University’s Teachers College. To graduate, you had to complete a master’s thesis. In practice, this meant a 25–50 page academic paper backed by dozens of citations.

My chosen topic focused on the cognitive science principles behind the Excel macro I had built in Panama to study Spanish, and how those principles could be applied through technology in a classroom setting.

When the Theory Outgrew the Tool

As I burrowed deeper into concepts like active recall, metacognition, and spaced repetition, it became increasingly obvious that my original Excel macro was not cutting it. It did not provide learners with immediate feedback; its algorithm did not properly manage cognitive load; and the learning data it produced was far too limited for an educator to actually use to better assist their learners.

It felt absurd to write a thesis simply about a hypothetical technology that should exist, especially after completing a dozen graduate courses that should have equipped me to make it. So even though it was not required for my thesis, I decided to build the real thing.

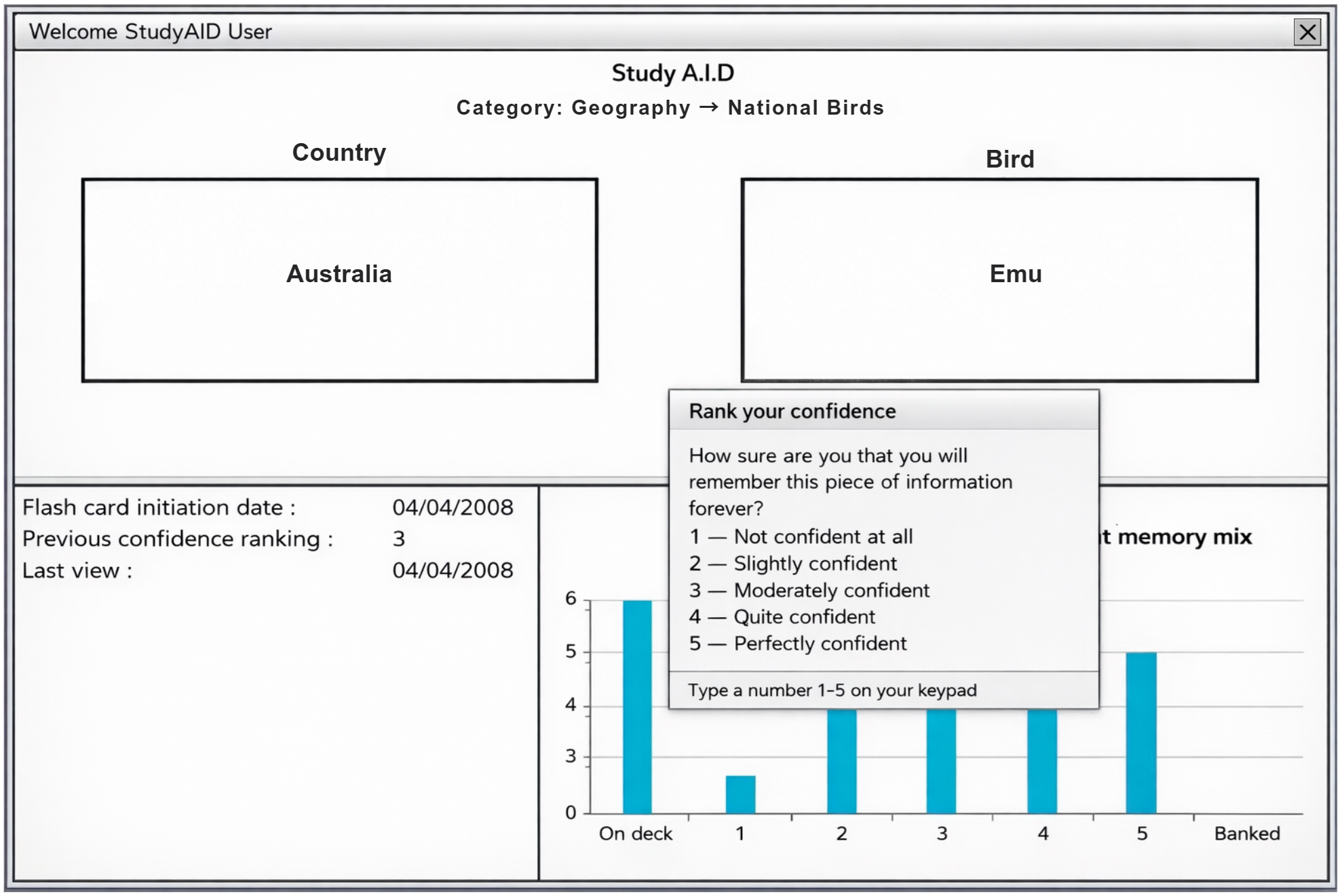

Over the course of a few weekends, I created Study A.I.D. (Assessment Interval Determination) as a desktop application in Java, with some help from my Java programming instructor, whom I paid on the side. The goal was to solve many of the interface and feedback problems that Excel simply could not handle.

The (Very 2008) Demo Video

I ended up being so pleased with the prototype that I even made this deeply embarrassing “commercial” for it as part of a Micromedia class project:

(I may not deserve an Oscar nomination for my role as "overwhelmed student", but I definitely deserve some kudos for resharing this embarrassing performance for the world to see.)

From Thesis to White Paper

Following the birth of Study A.I.D. (AKA baby Brainscape), I then wrote a master’s thesis that fully documented the software and its cognitive science foundations, citing several dozen peer-reviewed studies that proved the effectiveness of the cognitive science concepts that were built into the prototype.

The thesis was very well received by my advisors, and I graduated with distinction in 2008. That original work has since evolved into the Brainscape white paper, updated with even more recent academic research.

The Experiment

Going Beyond the Assignment

Unsatisfied with simply meeting the requirements for a research paper (and the extra credit I received for building a prototype), I felt compelled to validate whether people would actually want to use the thing I had created.

To do that, I designed one final, entirely non-required project for myself at Columbia, in the weeks after I had already graduated (but while my student ID was still considered valid).

The Focus Group Setup

I invited 12 fellow grad school friends to participate in a "focus group" where they would genuinely try the software. They were bribed with the standard university currency of beer and pizza.

The goal was to see whether Study A.I.D. was more effective (and/or engaging) than traditional paper flashcards at helping users retain information on a post-test.

Choosing What to Study

Most academic studies like the one I set up ask participants to memorize random word associations, such as Dog | Blue or Fan | Happiness, and then measure how many associations they remember.

I didn’t want to bore my friends with such useless information. I figured they should at least learn something real. The topic just had to be something that nobody knew anything about in advance.

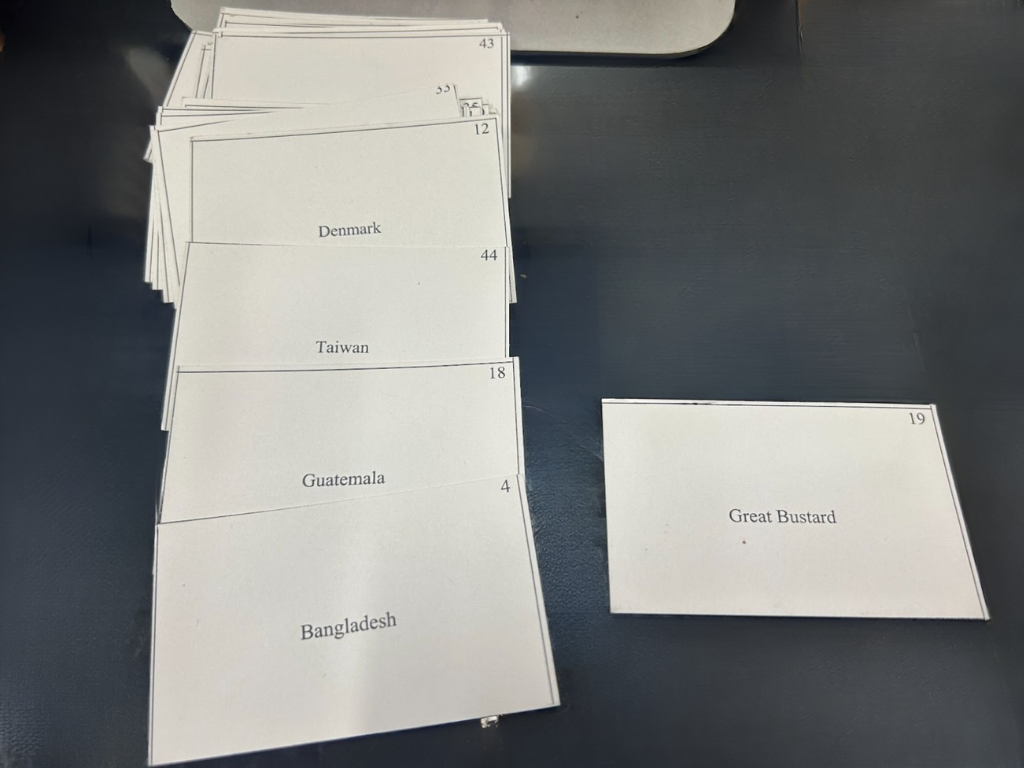

I landed on the perfect subject: countries and their national birds.

Dividing the Groups

I divided the participants into two halves. One group studied using paper flashcards, while the other studied using the Study A.I.D. prototype. The paper cards were pre-made, while the software had to be pre-installed on participants’ laptops, which they brought with them.

Two participants did not bring a laptop, and since I had run out of printed paper flashcards, they ended up using a simple printout listing all the countries and birds, studying however they wanted. This was effectively the equivalent of studying from a book and inventing your own method to retain the information.

The Test

I set a timer for 30 minutes and told everyone there would be a $20 prize for the highest score on the test that followed.

The Results

The average score of the Study A.I.D. group was more than twice as high as that of the paper flashcard group. In fact, the lowest score in the Study A.I.D. group was still higher than the highest score in the flashcard group.

This result was incredibly compelling. And it became the moment I decided to devote my career to building an educational tool that would help people massively improve their learning efficiency.

We had stumbled upon a study method that was remarkably effective, yet woefully underutilized in the real world. It had to be commercialized and made easier for people to use.

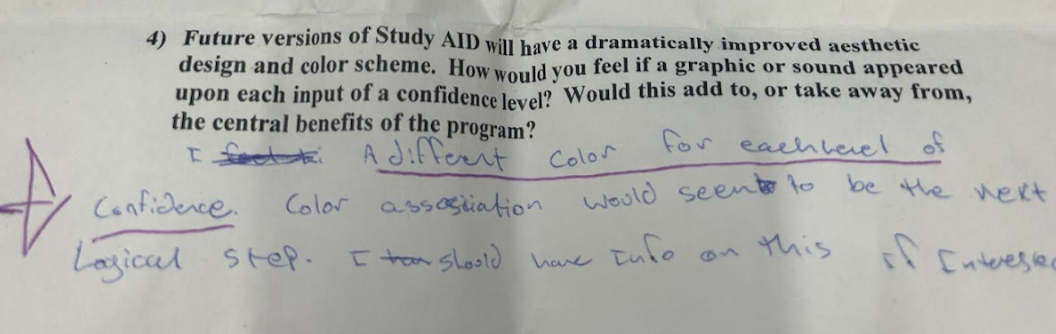

Luckily, I'd collected golden survey data from my participants that gave me great insight into how to improve the software going forward.

From 12 Guinea Pigs to Millions of Learners

Sadly, the pizza-and-beer study from my post-master’s experiment was not formal enough, nor did it involve a large enough sample size, to be published in an academic journal. (By that point, I had already graduated, so I no longer had the academic affiliation needed to rerun the experiment more formally.)

But since then, the Brainscape method has been validated in numerous more "real-world" case studies, not to mention tens of thousands of happy product reviews on the App Store, Google Play, and TrustPilot, as well as the massive body of ongoing research that Brainscape puts into the cognitive science concepts powering our software.

Brainscape Wants to Fund Your Research

And finally, we've created Brainscape Labs, where other cognitive science researchers and educators can apply for a grant to deploy Brainscape among your own students and measure the effectiveness in ways that make sense in your particular setting.

We are always committed to creating not only the most effective software but also the most practical and flexible to bring theory into practice.