This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

I have this little trick I do when reading fiction.

As characters get introduced, I jot down their names and a one-sentence description in a note app. (This is essential for the kind of three-inch thick epics I like to consume.) The idea is that if I ever forget who a character is or how they’re connected to the plot, I can come back and refresh my memory.

The funny thing is, I almost never have to.

The simple act of writing the names and describing them in my own words is enough.

But when I get lazy and skip this ritual, I find myself becoming tangled up: “Wait, who is this guy again?” and “How does she know her?” The plot becomes confusing. I forget who people are. My mental map collapses. And my enjoyment of the novel nose-dives.

I have abandoned MANY books because I simply, literally, lost the plot.

As it turns out, my small habit of writing down character names and descriptions is a perfect real-world example of generative processing. By generating meaning in my own words, I’m not just recording information, I’m reorganizing it, connecting it, and stabilizing it in memory. I’m processing it, which massively improves my retention.

At a much broader scale, understanding generative processing helps explain why some study techniques create lasting knowledge while others evaporate the moment you close the book. It also explains why digital flashcard apps like Brainscape lean so heavily on active, meaning-making study.

And so, in this article, we’ll break down the science behind generative processing and examine practical ways to design study or teaching experiences that encourage deeper processing, stronger connections, and far more durable learning.

Why bother? Cos we’re obsessed with the science of learning.

Let’s go…

What Is Generative Processing?

Generative processing is the mental work you do to create meaning from new information instead of hearing or reading it, and attempting to commit it to memory. It refers to any act of transforming information: summarizing it, explaining it to yourself, sketching it up as a concept map, making flashcards for it, teaching it, or retrieving it from memory.

In other words: you’re taking the information you’re learning and making sense of it.

In cognitive psychology terms, generative processing occurs when learners:

- Select the most important ideas

- Organize them into a meaningful structure

- Integrate them with what they already know

This is why passive techniques like rereading or highlighting a textbook can feel productive but rarely create durable learning. They expose your eyes to new information, but they don’t ask your mind to do anything with it. Generative techniques, on the other hand, force your brain to roll up its sleeves and get involved.

If you want a quick visual to demonstrate that contrast, the infographic below lays out the difference between passive study habits that feel productive and active strategies that actually build memory. It’s a handy reference as we get into what “generating meaning” looks like in practice.

Where Did the Idea of Generative Processing Come From?

Generative processing is the child of several influential cognitive theories that all point toward the same conclusion: learners aren’t empty containers, but active builders of understanding.

Jean Piaget and Jerome Bruner were early champions of this idea, arguing that knowledge isn’t absorbed but constructed. Later, Richard Mayer introduced models of multimedia learning that emphasized the learner’s need to select, organize, and integrate information for true comprehension to occur.

Meanwhile, John Sweller’s cognitive load theory showed us just how limited working memory really is, and why passive listening or rereading overloads our mental bandwidth. Generative strategies emerged as the antidote: by reorganizing information, learners create more efficient mental structures that reduce strain.

Fast-forward to today, and generative processing sits at the center of modern learning science. And across decades of research, one theme repeats: learning deepens when learners generate something—an explanation, a connection, a question, an interpretation—from the information they encounter.

How Does Generative Processing Work in the Brain?

Most generative learning activities share a common sequence of cognitive moves:

1. Selecting: Learners identify the most important ideas. This prevents cognitive overload by sifting out noise.

2. Organizing: Information is arranged into coherent structures: outlines, concept maps, storylines, or mental categories.

3. Integrating: New ideas are connected to prior knowledge, personal experience, or related concepts.

4. Elaborating: Learners expand on ideas using their own words, examples, or analogies. The brain makes the content its own.

5. Retrieving: Calling information from memory is itself generative, because each retrieval rebuilds the knowledge structure from incomplete cues.

Creating and studying flashcards using adaptive digital flashcard apps hits on ALL of these principles, which is why they’re such a powerful tool for fast, efficient learning but I’ll dive into that a bit more in a bit.

Why Does Generative Processing Matter for Learning, Teaching, & Memory?

In short, generative processing matters for learning, teaching, and memory because it is one of the most reliable ways to create long-term, transferable knowledge. Here’s why…

It turns exposure into understanding.

Students often mistake familiarity for mastery. Rereading feels productive because concepts start to look familiar. But generative methods force the brain to interpret and restructure that knowledge, which is what actually leads to durable learning.

It strengthens encoding.

When you elaborate on an idea, you activate broader neural networks. Memory systems love redundancy. The more pathways you use to represent knowledge, the easier it will be to retrieve later.

It integrates new and old knowledge.

Explaining something in your own words requires you to connect it to existing mental frameworks. Neuroscientific studies (like Van Kesteren et al., 2020) show that reactivating prior knowledge during learning improves integration and retention.

It reveals misunderstandings early.

When you try to explain a concept and stumble, that friction is feedback. It shows where your understanding falls short; where your mental model is shaky. This avoids the classic “I thought I understood this until I had to actually use it” nightmare.

It reduces cognitive overload.

By condensing new information into meaningful units, generative work frees space in working memory. In other words, instead of juggling dozens of loose facts, your brain can focus on a smaller number of well-organized ideas that are far easier to manipulate and remember.

It improves transfer.

Because generative work integrates ideas deeply, learners are more likely to apply them in new contexts. This ability to generalize is one of the hallmarks of expert knowledge.

Overall, it makes learning more efficient.

When the brain generates its own meaning, it reduces the need for excessive repetition. You’re not memorizing individual facts. You’re building a network that supports retrieval with less effort over time.

Now that I’ve thoroughly sold you on the benefits of generative processing as a principle for efficient learning, how can you integrate it into your study routine (or that of your students, if you’re an educator)?

There are several ways, and we’ll get to them shortly, but the most powerful is with the humble flashcard! (Or “notecard” if you’re from the UK.)

How Do Flashcards Leverage Generative Processing?

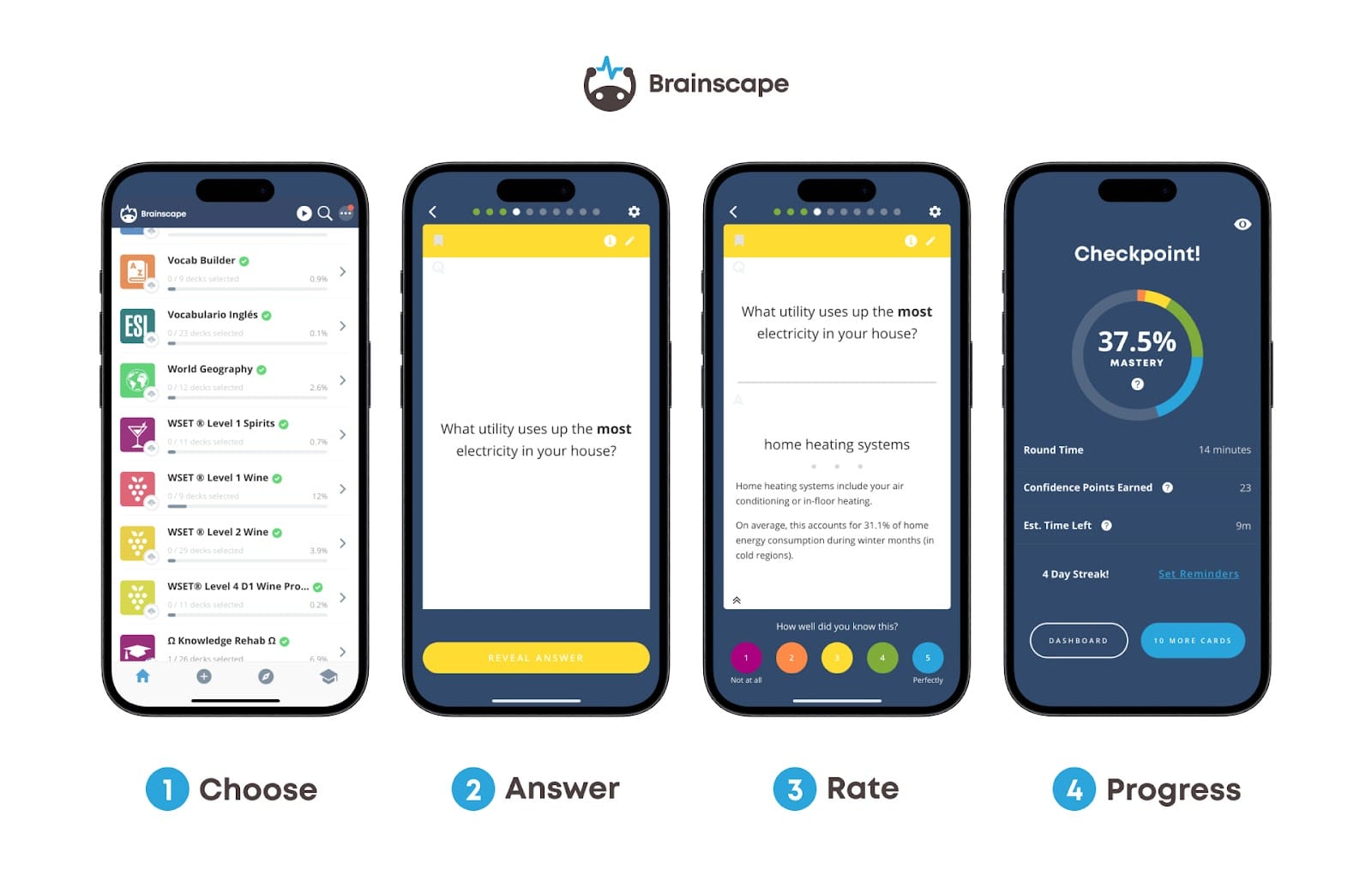

Flashcards are natural vehicles for generative processing; particularly adaptive, digital flashcards, which integrate a suite of other learning principles, such as spaced repetition, active recall, metacognitive feedback, and variable rewards, and more.

(In fact, for the complete story of how flashcards embody the science of studying, check out the linked article.)

Anyway, back to how digital flashcards leverage generative processing. Here’s why they’re such a great tool for these kinds of learning exercises…

- Every time you answer a flashcard, you’re not just recalling information. You’re rebuilding the idea from memory, which strengthens the encoding pathways.

- Flashcards break information into discrete conceptual units, nudging the brain to select key ideas and structure them meaningfully, not only in individual flashcards but also into decks organized by topic or subject.

- Repeated retrieval across time forces the brain to reconstruct knowledge on multiple occasions, each time enhancing the stability of the memory.

- When creating flashcards, learners often rewrite or personalize them to include their own examples, questions, media (like audio and images), and explanations. This active elaboration is one of the core mechanisms of generative processing; one that turns isolated facts into meaningful, well-wired knowledge structures.

Many flashcard apps support multimedia, allowing learners to take simple black-and-white concepts or vocabulary and bring it to life with audio and/or visual accompaniments.

Platforms like Anki and Brainscape embody these principles by combining spaced repetition with active engagement, helping learners apply generative processing naturally every time they study.

What are Some Other Ways to Apply Generative Processing?

Generative processing thrives in any environment where students do the cognitive heavy lifting. A few effective ways to put it into practice:

Self-explanation: Pausing during reading or problem solving to articulate why something works. This doesn’t need to be a TED Talk. Even quick, muttered explanations are enough to strengthen understanding.

Retrieval practice: Using digital flashcards, quizzes, or simple question-generation forces the brain to reconstruct meaning instead of re-exposing itself to information. Retrieval is generative by nature because you must rebuild the memory trace each time you call it up (Fiorella & Mayer, 2016).

Analogies and metaphors: Whenever learners compare a new idea to a familiar one, they integrate it into existing neural networks. Analogies are like cognitive Velcro: they help information stick to what you already know.

(Here’s an example: if you’re learning about electrical circuits, comparing them to water flowing through pipes instantly gives the new concept something to latch onto. Voltage becomes water pressure, current becomes the flow rate, and suddenly the unfamiliar system feels far easier to grasp.)

Summaries and paraphrasing: Writing a short summary is like wringing out a soaked sponge until only the essential meaning remains. It also reveals where comprehension is still fuzzy because if you’re struggling to explain a concept in simple terms—and in your own words—then you clearly don’t understand it well enough!

Sketching and diagramming: Translating concepts into visual form triggers dual coding and helps the brain organize relational information spatially.

Transforming notes rather than transcribing: Reformatting notes into outlines, concept maps, question-and-answer pairs, or flowcharts promotes deeper reasoning than copying text verbatim.

These techniques work because they invite the learner into the process as an active participant, rather than a passive bystander.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Generative processing is the behind-the-scenes cognitive wizardry that transforms information from something you’ve seen into something you understand and remember. It explains why writing your own summary sticks better than rereading a chapter, why teaching someone else clarifies your own thinking, and why flashcards remain one of the most efficient learning tools ever invented.

When you engage deeply with new information (by selecting it, organizing it, connecting it, elaborating on it, and retrieving it) you build knowledge that lasts.

Generative processing is just one of many learning-science concepts that illuminate how your mind works, and how you can work with it rather than against it. The more you understand these principles, the more efficient and enjoyable your learning becomes!

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading (if you’re a sucker for punishment)

If you loved this article, you’ll also love these other nerdy science articles we wrote about:

- What is Cognitive Load Theory? (& Why Does Too Much Info Hurt Learning)

- The “What the Hell" Effect & How to Conquer Its Vicious Cycle

- What is Spaced Repetition (& Why Is It Key To All Learning)?

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

References

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31(1), 21–32. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1962-00777-001

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717–741. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-015-9348-9

Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19.

Mueller, M. L., Tauber, S. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2022). Why does self-explanation improve learning? A meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 48(9), 1296–1316.

Pan, S. C., & Rickard, T. C. (2022). Transfer of test-enhanced learning: Meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 148(5–6), 265–293.

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Trans.). International Universities Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-10742-000

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255.

Van Kesteren MTR, Krabbendam L, Meeter M. Integrating educational knowledge: reactivation of prior knowledge during educational learning enhances memory integration. NPJ Sci Learn. 2018 Jun 25;3:11. doi: 10.1038/s41539-018-0027-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30631472/

Zhang, J., Kuhn, D., & Schneider, W. (2021). Elaborative interrogation supports knowledge integration in adolescents. Learning and Instruction, 74, 101442.