This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

You’ve been there: sitting in front of your notes, rereading the same paragraph for the third time, and thinking, “Okay, I totally get this.” Then, the next day, in the middle of your test, you blank completely and think: “Sh**—I didn’t really know it, did I?”

That internal whisper is metacognition in action. Thinking about your thinking.

Metacognition is your brain’s inner coach, the part that monitors what you understand, calls out what you don’t, and, if you actually listen to it, helps you make smarter decisions. It’s that quiet mental voice that says, “I need to work on X” or “I’m getting good at Y” or “I should stop binge-watching Love Is Blind and get back to my assignment.”

Most people ignore that voice; great learners train it.

Understanding how to think about your thinking can completely transform how you remember, reason, and learn, not just for exams, but for everything, from mastering a second or third language to navigating real-life problems.

And since metacognition is so integral to fast, effective learning, here at Brainscape, we're on a bit of a crusade to help anyone who still actually reads articles to deeply understand what it is and how to leverage its potent power to drive change.

Let’s begin with a more sciencey explanation of…

What Is Metacognition?

Metacognition is often summarized as “thinking about thinking”, your brain’s built-in autopilot for self-monitoring and steering your learning. It’s the difference between passively reading a textbook and actively asking yourself, “Do I really get this?”

In practice, metacognition includes things like:

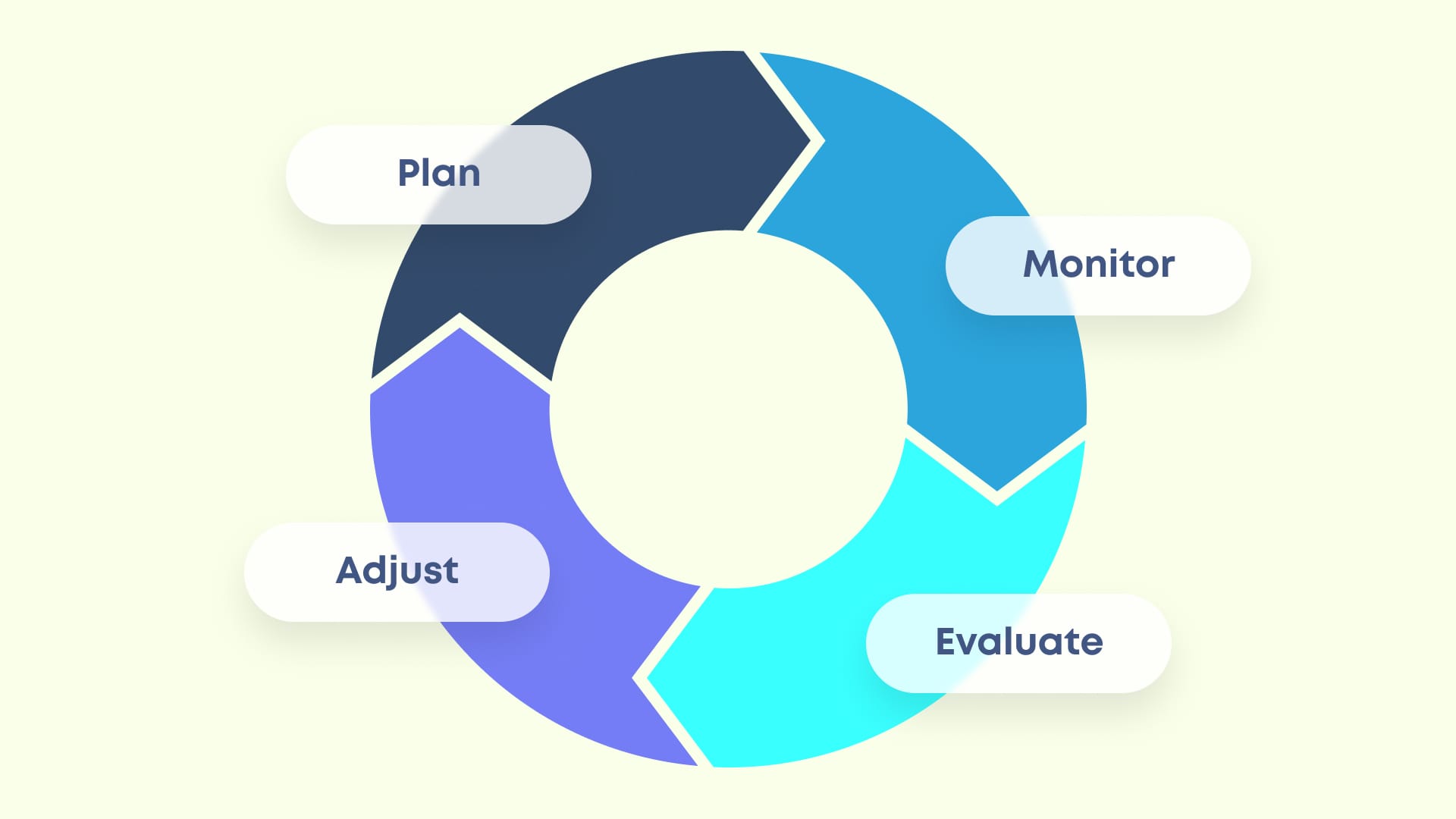

- Planning how you’ll approach a study session

- Monitoring your understanding as you go

- Evaluating afterward: what worked, what didn’t, and how you should adjust

(I’ll tell you all about an effective and accessible study tool to facilitate metacognition shortly.)

When you ask yourself, “Does this make sense?” or “Should I go back and review that section?”, you’re engaging in metacognition. And when honed, it becomes one of your most powerful learning tools.

So, who originally thought up this thought about thinking about your thinking? (Say that three times fast.)

Where Did the Idea of Metacognition Come From?

The term metacognition is often credited to John Flavell (1970s), who studied how children become aware of their own thinking and memory processes. Over decades, researchers like Ann Brown, Joseph Campione, and others expanded that into educational theory: metacognitive strategies, self-regulated learning, and so on.

In more recent years, cognitive scientists and educators have continued refining the concept, linking metacognition to memory, attention, and even brain imaging studies, like in this study: “Metacognition: ideas and insights from neuro”.

Because metacognition sits somewhere above cognition (meta means “beyond”), it’s often considered a higher-order skill that you can strengthen, and that’s exactly why it’s so powerful for learners and educators alike.

How Does Metacognition Work, Cognitively?

To see how metacognition operates, imagine your learning process as driving a car on a winding road. Metacognition is your dashboard: speedometer, GPS, warning lights, all giving you feedback, alerting you to danger, and helping you adjust.

Here’s how it works behind the scenes:

- Metacognitive Knowledge: What you know about yourself, your strategies, and when to use them. Example: “I learn biology better if I draw diagrams rather than just reading.”

- Metacognitive Monitoring: The ongoing assessment of how well you understand something. Example: “Wait, I can’t explain how this works. Maybe I need to review that part.”

- Metacognitive Regulation / Control: Deciding what action to take (revisit, skip, elaborate) and when. Example: “I’m still shaky on this chapter, so I’ll slow down or make flashcards for it.”

Neuroscientific and cognitive work point towards metacognitive monitoring being connected with your brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive functions like planning, decision-making, and impulse control. People with stronger metacognitive skills also show better attention allocation and error detection.

In short: metacognition sits in the executive suite, constantly checking, correcting, and guiding your study journey.

What Are the Key Components of Metacognitive Strategies?

For learners and educators, metacognitive strategies are the levers you can pull to make metacognition work for you, in practice. In other words, if you try to incorporate some of the following suggestions, you will find yourself being so much more effective in your learning and/or your teaching.

But, remember, this extends far beyond learning/teaching in the classroom! Wherever you are in life, engaging these metacognitive strategies will serve you tremendously well:

- Self-questioning / Reflection Prompts: When attempting to learn and remember something new, ask yourself: What do I understand? What’s confusing? How will I test that? (You could do this with a chapter in a textbook or a new skill at work.)

- Think-Aloud Protocols: As you solve a problem or read, verbalizing (or mentally verbalizing) your reasoning helps expose blind spots in understanding. In other words, try to speak or think in a more narrative way about the problem or piece of information. This will help you identify gaps in your reasoning.

- Monitoring with Prediction: Before you review or test yourself, predict your performance. Then compare your prediction to your outcome. That feedback sharpens the calibration of your metacognition so that, in the future, when you make predictions about what you know (and how well you know it), it’ll be more accurate.

- Planning and Goal Setting: Before studying, set explicit short-term goals: “I’ll master these five concepts in 30 minutes.” This boils down to pure motivation. Understanding the goalposts as you sit down to learn something will motivate you to accomplish the task.

- Adaptive Strategy Adjustment: If your monitoring shows you’ve misunderstood something, shift your strategy. Go back and re-read, make flashcards, identify analogies that help the concept stick, or even draw diagrams or concept maps. It’s not good enough to arrive at the conclusion “I don’t know this all that well”. You then need to do something about it.

- Post-mortem Evaluation: After a study session, practice test, or real life exam, reflect: What worked? What didn’t? What should I do differently next time? Sure, it’s tiring! That’s the point. If it requires cognitive energy, it’s working! You’re being active in your learning rather than passive, and that will help you make faster progress.

In classroom settings, instructors can scaffold these processes by embedding prompts, reflection time, and modeling the “thinking aloud” process for students.

Now let’s talk about that study tool I mentioned earlier: the one that probably does the best job of leveraging metacognition to help you learn more efficiently…

How Do Digital Flashcards Leverage Metacognition?

Digital flashcard apps like Brainscape, Memrise, or Anki are one of the cleanest, most scalable ways to embed metacognition into everyday learning. Here’s why…

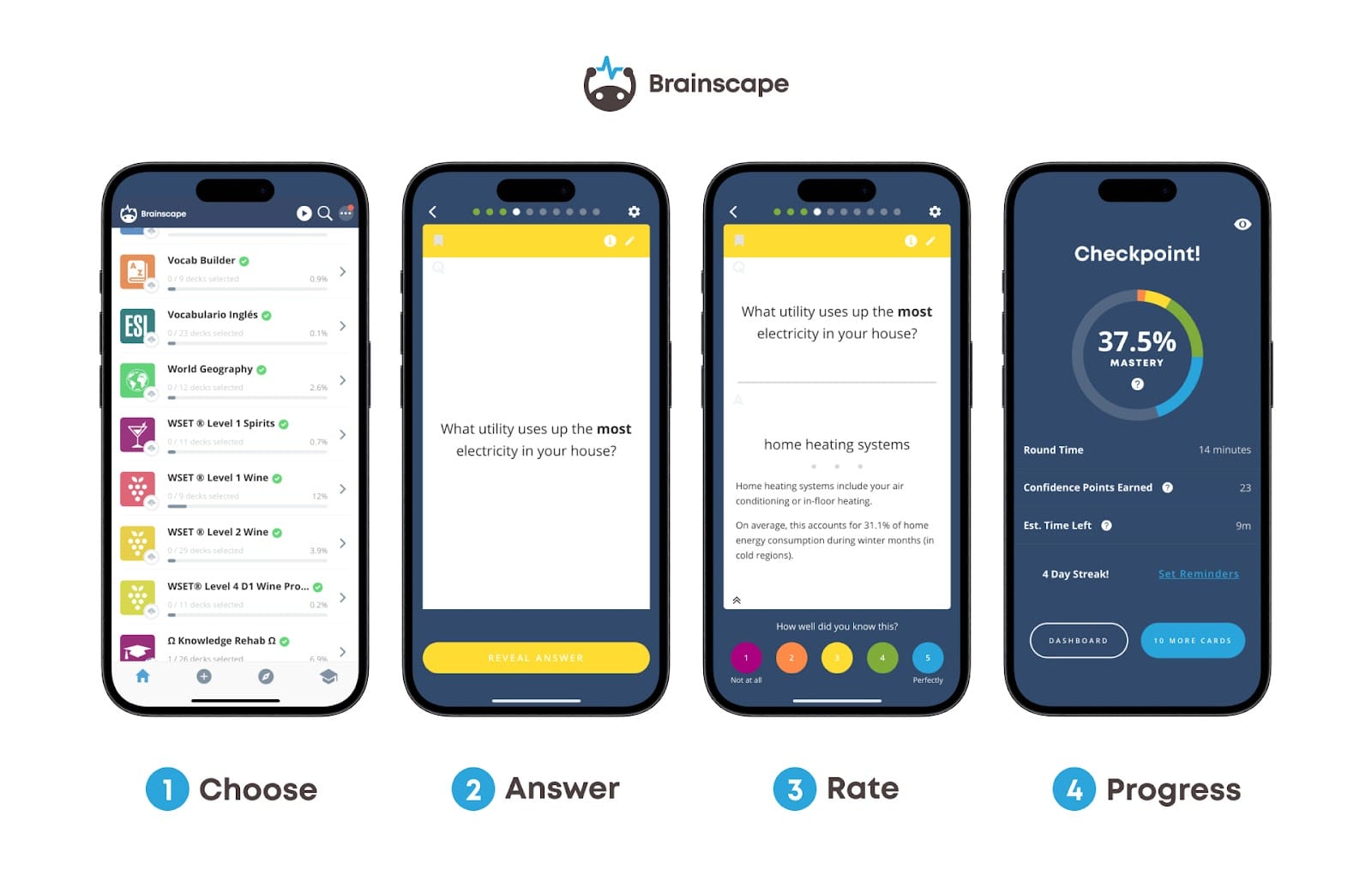

A flashcard shows a question based on a single concept or piece of information. You attempt to answer that question “from scratch” without the assistance of any multiple-choice answers. Then, you flip the card over to reveal the answer, at which point you are required to rate how well you knew it. In Brainscape, for example, you’re required to rate your confidence level on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being “I didn’t know this at all” and 5 being “I knew this perfectly and will never forget it”.

This—the act of rating how well you knew something—is metacognition at work. This is why these flashcard apps are such efficient learning tools: because compelling you to exercise your powers of metacognition deepens your learning of the content much faster than if you just passively reviewed it.

Here are some other ways that digital flashcards leverage metacognition:

- Confidence Ratings = Real-Time Monitoring: After each card, you rate your confidence. That is literal metacognitive monitoring — “Do I think I got this right?”

- Adaptive Spacing and Review = Regulation: When you rate a flashcard a 1 or 2, the study algorithm resurfaces it more often. When you rate a 4 or 5, it fades it away. That is metacognitive regulation built into the tool (provided the tool you’re using has spaced repetition built into its study algo).

- Forcing Recall, Not Rereading: Active recall (vs passive rereading) forces a more honest assessment of your knowledge. You can’t trick yourself into thinking you understand something unless you can produce that knowledge.

- Layered Complexity: Scaffolding: Flashcards can build from simple fact cards to more integrative concept cards. You scaffold within the deck itself, letting metacognition guide how you step up difficulty.

To sum it all up, digital flashcard apps (and there are many out there, but few with the sophistication of Brainscape and Anki) don’t just test you, they teach you how to monitor and regulate your own study process.

Do you see now why I say they’re one of the best study tools?

Why Does Metacognition Matter for Learning, Teaching, and Memory?

Not to mince my words or anything, but why should you give a damn about any of this?

Well, metacognition matters because it turns passive exposure into purposeful processing. In other words, it’s the secret to faster, more effective learning, whether it’s for a biology test or to impress the socks off your boss.

With the metacognitive strategies we’ve explored above, you’ll be able to:

- Better Focus Your Efforts: You don’t waste time re-reading what you already know. You prioritize weak spots.

- Enhance Encoding & Retrieval: By monitoring and adjusting, you often force more effortful processing (which strengthens memory).

- Reduce Overconfidence / Illusions: Many students feel they’ve learned something when they haven’t (the “fluency illusion”). Metacognition bridges that gap.

- Transfer and Flexibility: Strong metacognitive learners apply and adapt these strategies across domains. Some training studies find that metacognitive regulation can transfer to new tasks.

There’s a ton of empirical support for all of this in modern research.

In nursing education, higher metacognitive regulation predicts better clinical decision-making over time (BioMed Central).

In biology education, a metacognition-based 10-week course improved both metacognitive awareness and biology comprehension (Frontiers).

A recent bibliometric study on metacognition research maps emerging trends in educational metacognition and calls for more instructional designs that facilitate metacognitive skills (SpringerLink).

So, What’s the Takeaway?

By planning, monitoring, and evaluating your learning process, metacognition turns inefficient cramming into strategic exploration. You’re learning how to learn, not just what to learn.

And one of the best tools that automate metacognition are flashcards, particularly digital flashcards. When used thoughtfully, they act as micro-metacognitive instruments, nudging you to constantly assess and adjust. Over time, your internal “dashboard” gets sharper and more intuitive.

So, if you’re ready to level up your remembering power, remember this:

- Don’t just read: plan, monitor, question.

- Use tools that force retrieval and self-assessment, like flashcards.

- Reflect on what works, what doesn’t, and tweak your approach.

When you do, your brain becomes its own tutor, gradually eliminating guesswork and wasteful study habits.

Additional Reading

Don’t stop here! Keep nerding out over how your brain actually works with these awesome reads:

- What Is Confidence-Based Repetition (& How Can I Massively Boost Grades)?

- Resolution & Judgments of Learning: What They Are & Why They Matter

- What is Cognitive Load Theory? (& Why Does Too Much Info Hurt Learning)

- Additional Reading (if you’re a sucker for punishment)

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

References

Brown, A. L. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. In F. E. Weinert & R. H. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and understanding (pp. 65–116). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dangremond Stanton, J., Sebesta, A. J., & Dunlosky, J. (2021). Fostering Metacognition to Support Student Learning and Performance. CBE—Life Sciences Education. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-12-0289

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Metacognitive processes, situational factors, and clinical decision-making in nursing education: a quantitative longitudinal study. (2024). BMC Medical Education, 24(1530). https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-024-06467-y

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 26, pp. 125–173). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60053-5

Sadykova, A., et al. (2024). The impact of a metacognition-based course on school students’ metacognition and biology comprehension. Frontiers in Education. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/education/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1460496

“Metacognition research in education: topic modeling and bibliometrics.” (2025). Educational Technology Research & Development. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11423-025-10451-8

“Metacognition: ideas and insights from neuro.” (2021). npj Science of Learning.https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-021-00089-5Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist.