Imagine yourself in Beijing, conversing easily with your business partners in Mandarin. Or at a vineyard in France, where the owner is describing the complex flavors of a deep Bordeaux. Or at a packed bar in Grenada, ordering tapas and sangria for your friends. Languages open doors to a ton of unique and wonderful authentic cultural experiences.

There’s just one problem: they’re difficult to learn.

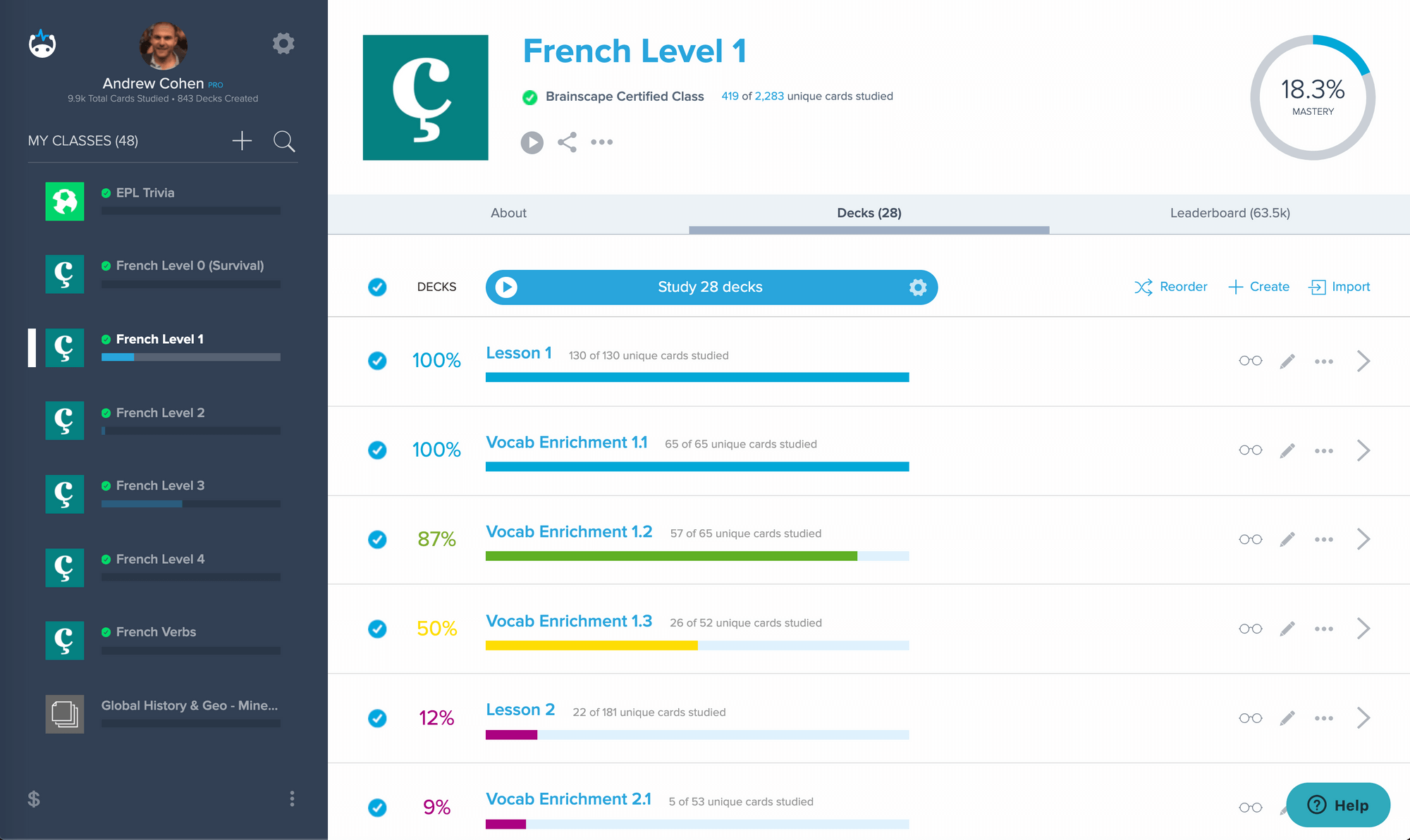

We know that better than anyone. Brainscape was born out of the struggle to learn a language: our CEO Andrew Cohen developed an early version of Brainscape to help him learn Spanish. We know that there’s no easy way to learn a language.

But we also know that some methods are more effective than others. Spaced repetition language learning is one of them.

Brainscape was developed to make learning a language as effective and efficient as possible. While creating our popular adaptive flashcard platform, we’ve been obsessed with understanding and applying principles of cognitive science to optimize learning. That obsession stretched to language learning. What's the result?

A system that teaches languages as fast as possible using cognitive science.

We've developed innovative Learn French, Learn Spanish, and Learn Chinese (Mandarin) programs using this system (with other languages coming soon). We are confident that these are now the most advanced and effective systems for learning those respective languages on the internet, combining a series of groundbreaking, proven atomic exercises that have never before been fused into a web and mobile language-learning tool.

To date, over 1 million independent language learners have used Brainscape's Intelligent Cumulative Exposure (ICE) system for Spanish and French and have had extremely positive things to say. But besides such amazing feedback, how can we be so certain that we’re offering the best way to learn a language? Because we’ve worked together with language scientists and teachers to design them carefully to be consistent with the best research on how we acquire language.

This article explains how we’ve created a revolutionary system for language learning based on cutting edge research and carefully crafted systems combining spaced repetition, a complete language curriculum, intelligent cumulative exposure, and adaptability. We’re going to cover the aspects of Brainscape that make it the best language learning tool out there:

- Spaced repetition for language learning—the right way

- What's missing in spaced repetition for foreign language acquisition?

- A carefully designed “Intelligent Cumulative Exposure” curriculum

- Your fastest path to foreign language fluency

So if you want to learn more about how Brainscape uses brain science to help you learn a language faster, let’s dive in.

1. Using spaced repetition for language learning—the right way

The core of the Brainscape learning system is our flexible spaced repetition algorithm. It’s our “secret sauce”.

Spaced repetition is the technique by which new or difficult concepts are studied more frequently than easier known concepts, then repeated in increasingly longer intervals the better you know them. It is the most important breakthrough in the science of learning the past century.

Adequately spacing repetition has been shown to be tremendously more effective than any other "memorization" gimmick like mnemonics, stories, emotions, or associations. Indeed, when combined with the user's own self-assessment and applied to a massive body of knowledge like law, medicine, or a foreign language, spaced repetition can literally help people learn many times faster and retain the information for exponentially longer.

The intuitive effectiveness of this technique has accordingly led software developers to create hundreds of spaced repetition language learning flashcard apps over the years, in which you can easily make your own flashcards, import your own lists, or find flashcards created by others.

And it is only natural that foreign languages have become among the most common applications of these spaced repetition apps, typically for vocabulary memorization.

2. What's missing in spaced repetition for foreign language acquisition?

The problem is that most foreign language educators and learners have historically thought of spaced repetition as simply a "feature". What they overlook is that spaced repetition is not some silver bullet that you can just strap onto a game or a giant list of vocab flashcards and hope to magically reach the promised land of fluency.

Spaced repetition is only effective when combined appropriately with the actual curriculum in which the knowledge is initially presented.

By far, the most important component of a spaced repetition language-learning journey is the order of initial exposure of bite-sized learning concepts—the careful, incremental introduction of individual words and grammatical constructs in just the optimal pace for your current level, while systematically repeating previously learned concepts with just the right level of frequency and mental engagement so that you're constantly building and not forgetting the knowledge.

Brainscape has addressed precisely this void. We have developed a foreign language acquisition curriculum that has been built specifically for spaced repetition.

With Brainscape's adaptive flashcards, spaced repetition is not a "feature". It is the product itself, and the curriculum is baked into that product, with the flexibility for the learner to add their own acquired concepts to that curriculum on the fly.

3. Introducing "Intelligent Cumulative Exposure"

We call this intimate combination of an obsessively incremental curriculum with an obsessively optimized spaced repetition algorithm: "Intelligent Cumulative Exposure" (ICE).

What is it about the Brainscape ICE language curriculum that makes it such a popular spaced repetition foundation for any independent foreign language learner? As mentioned earlier, there are four major advantages (all of which make use of our sophisticated spaced repetition algorithm):

- A practical progression of concepts

- A relentless focus on production

- Multiple modes of incremental exposure

- Adaptability to your own experiences

Let's dive into each ICE advantage in some detail, with an eye to the cognitive science benefits provided by Brainscape's unique combination of curriculum and spaced repetition.

3.1. A practical progression of concepts

First and foremost, concepts in Brainscape's ICE-based language curriculum are painstakingly ordered from "most practical" (most likely to be needed in basic conversation) to "most specific", throughout the entire program. We developed this flashcards progression based on deep analysis of language corpora and a survey of our own language learners who rated the "usefulness" of thousands of thousands of keywords and grammatical concepts.

This is in stark contrast to how most textbooks, courses, or language apps teach concepts, which tend to be purely by "topic".

For example, a beginner lesson in a typical language app might be for a topic like "Family Words". In that same lesson, you might be learning common words like "mother", "sister", and "child" but also other less common words like "grandmother", "niece", and "uncle", which are significantly less likely to be needed so early in your language-learning journey.

This grouping by topic area may sound logical, but it is a huge waste of your precious time early in the learning process! If those less useful "secondary family words" like "grandmother", "niece", and "uncle" were words # 53-55 that you had learned in German, wouldn't those early slots have been better spent learning more immediately useful words like "money", "bathroom", or "boyfriend"?

The fact is, grouping grammar by many sub-optimal topics is ultimately an inferior rate of learning than if you were to be learning the language "on the streets", on a need-only basis.

Brainscape's ICE foreign language curriculum tries its best to mimic the natural need-based progression of exposure by obsessively organizing concepts from the most fundamental to the most esoteric, but still with some chunking (such as "basic family words") within a typical level grouping. As research shows, the more practical the concepts learned, the more likely the learner will maintain their language-learning motivation.

[Want more than flashcards? Check out our complete language-learning toolkit]

3.2. A relentless focus on production

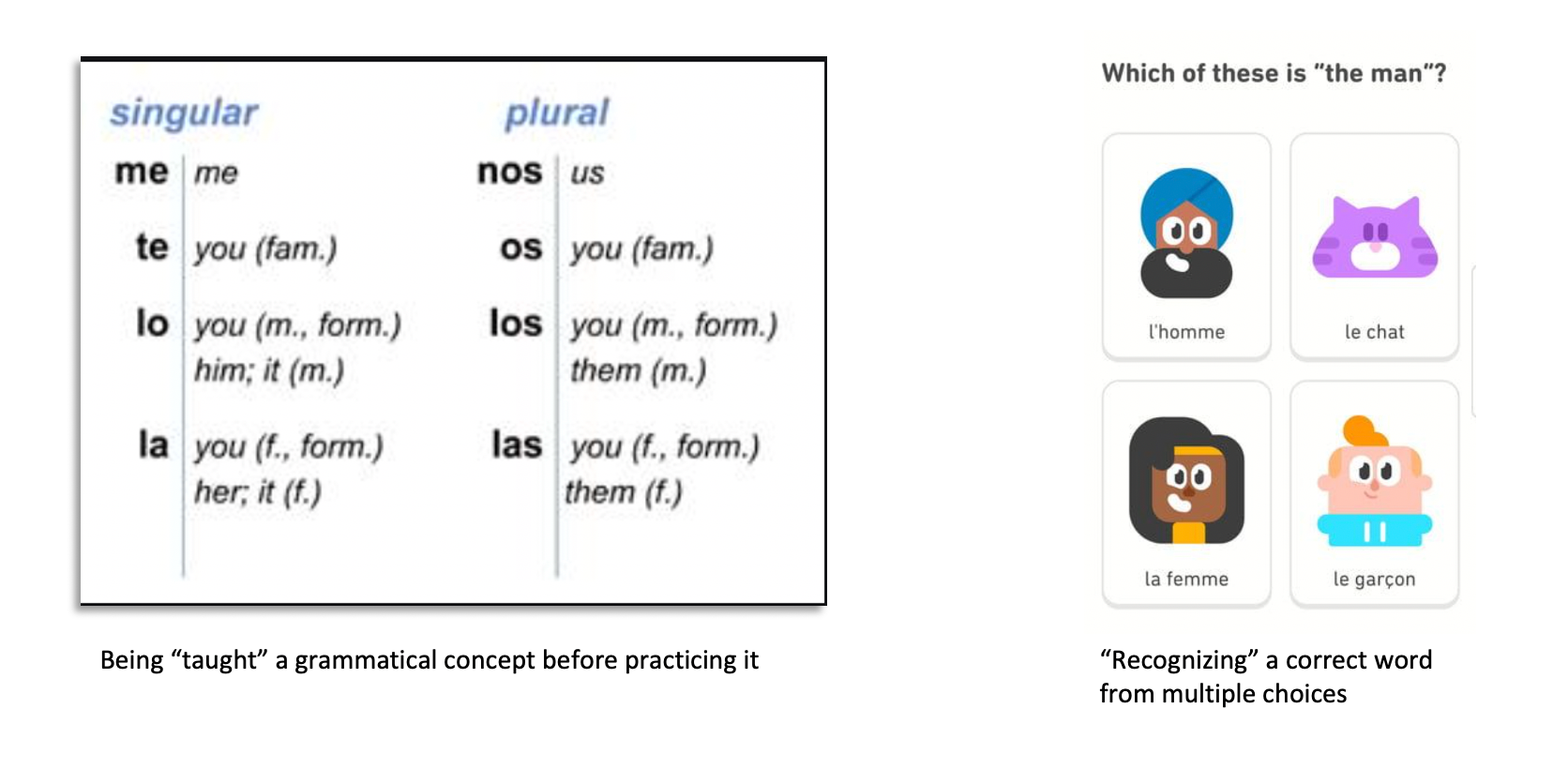

The typical foreign language textbook or app begins a lesson by first showing the user the language concept, i.e. by providing "input." You may have seen exercises like these at the beginning of a language lesson:

Beginning a lesson with such activities may seem to make sense. First you "teach" a concept. Then you ensure that the learner can "recognize" the concept. Only then could you start doing exercises to "practice" the concept. Right?

WRONG! In the real world, you are most likely to remember a concept when you first need to say it (aka "production"), you try to say it (or remember it using active recall, you fail to say it, and only then you are corrected with the proper words and pronunciation (and potentially a grammatical explanation).

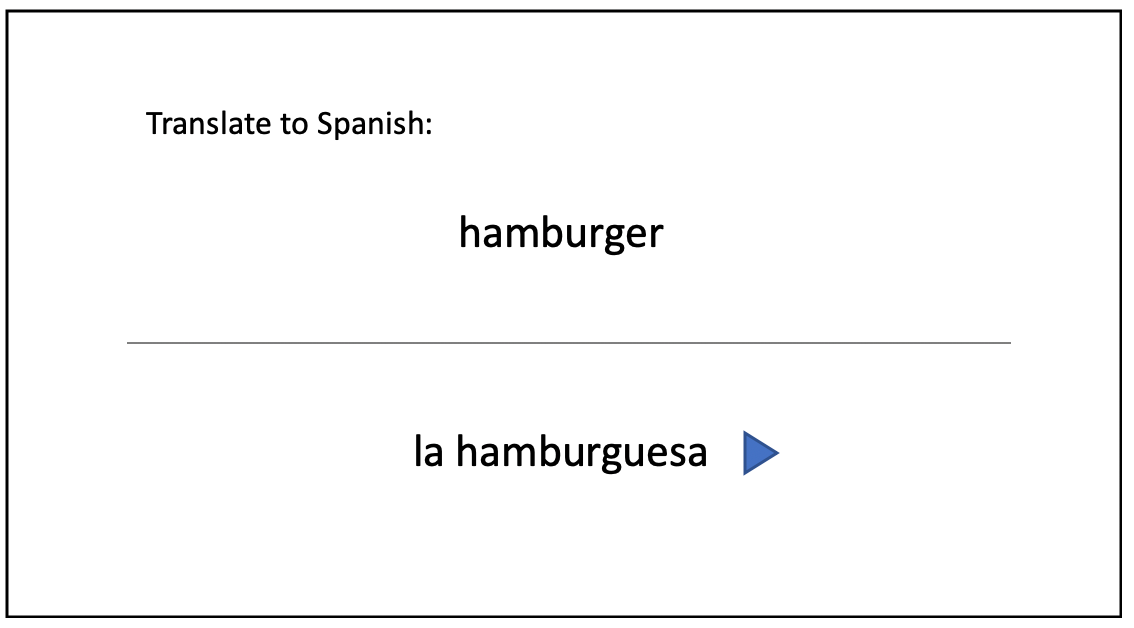

Brainscape ICE curriculum mimics this real-world experience by asking you to actively recall the phrase based on nothing but a native language prompt (e.g. "hamburger") and then—once you are ready to reveal it—showing you both the correct spelling and the correct audio playback with an authentic native speaker at a naturally spoken speed.

Research suggests that the act of attempting to produce phrases in the target language is most effective in helping second language learners to "recognize consciously some of their linguistic problems.” Other researchers have further confirmed that learners are naturally more likely to perform subconscious metalinguistic analysis of the grammatical rules behind a sentence when the learner herself is the one actively producing that sentence. Still others have concluded that as the learner utters and analyzes her own words, she refines her understanding of their structure, especially when corrective feedback is given.

Brainscape's progression of production, correction, and explanation is thus a scientifically optimal flow and is similar to how an actual conversation with a native speaker would be if that native speaker could give constant feedback on a sentence-by-sentence basis. Studying with Brainscape's ICE curriculum is like having a tutor with you at all times.

3.3. Multiple modes of incremental exposure

Learning a new language is about so much more than "memorizing words." But someone forgot to tell that to most of the fun language-learning games, apps, and free flashcard decks out there. The majority of language apps are almost entirely vocab focused, with only incidental grammar learning, since their interfaces are set up for trying to assess you with cute scores and leaderboards.

In contrast, Brainscape's open flashcard canvas—where you simply think of the answer in your head before revealing it (and rating your confidence) rather than choosing from among multiple choices—provides us the flexibility to provide new types of vocabulary and sentence-building exercises that would be simply incompatible with other interfaces.

In each type of Brainscape ICE exercise, the flashcards are designed to be perfectly incremental, so that there is only one new learning objective per flashcard. Although concepts are repeated in their own specified intervals after their first exposure, new concepts are always displayed in the Brainscape-defined order. No supporting word or concept may be casually used in a sentence unless it has been previously explained, and no new concepts are introduced until the user’s confidence in previously taught concepts has reached a sufficient level.

This piecemeal progression conforms to Krashen's famous admonition that an incremental approach is the most effective way to maximize mental processing of new language concepts while minimizing cognitive load. According to Krashen's Input Hypothesis, each chunk of input should be presented at a level of difficulty equal to i + 1, that is, just a bit beyond the learner’s current ability (i), but not so difficult as to seriously impair comprehension nor so easy that no new language challenges are encountered.

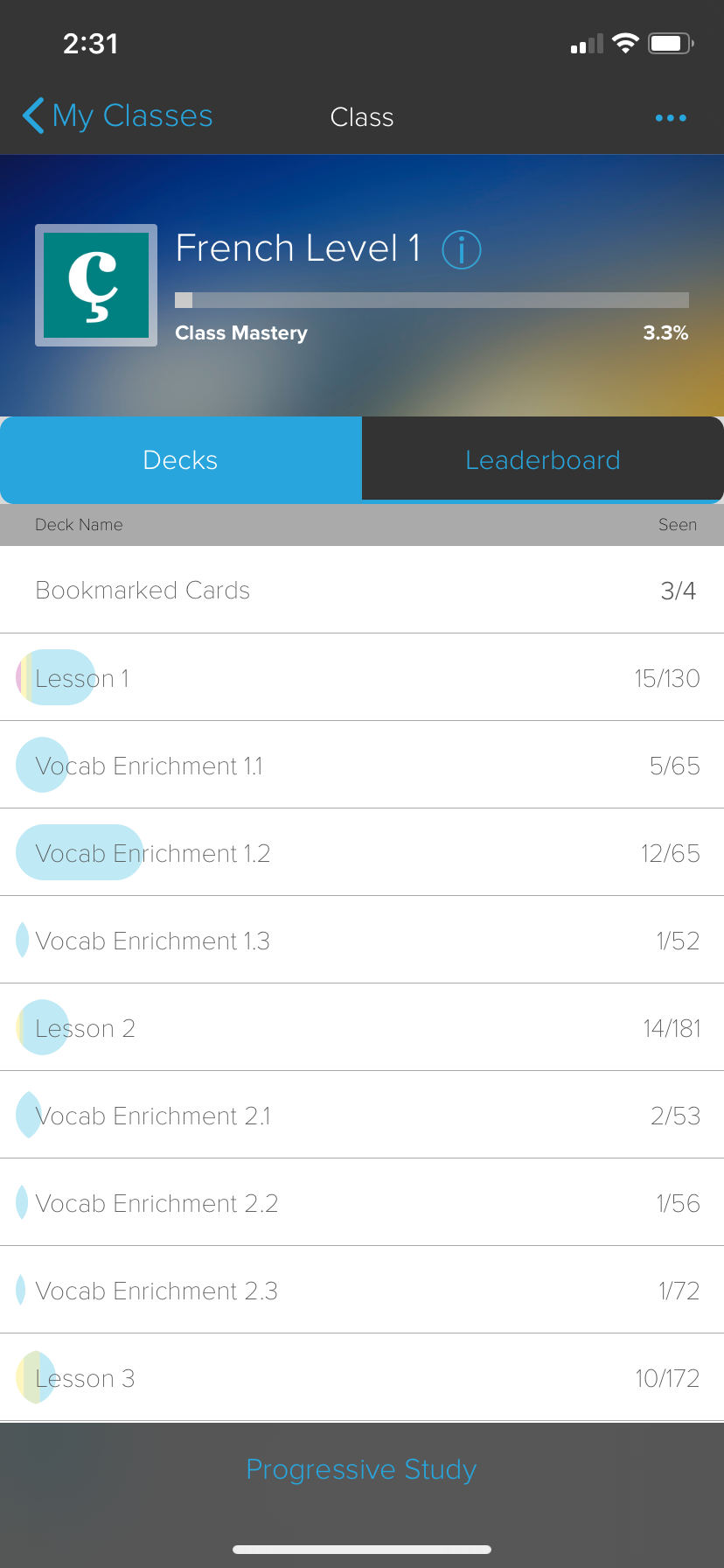

Let's take a deeper look at the three unique, alternating flashcard deck types that comprise Brainscape's ICE foreign language curriculum: Sentence Builder, Vocab Enrichment, and Listening Practice decks.

3.3.1. Lesson (aka "Sentence Builder") decks

Typically, when we hear a new sentence in a foreign language we are trying to learn, there are a number of words or concepts with which we are unfamiliar. While this may be a "natural" means of exposure, it is a vastly sub-optimal progression. A sentence with 5 new words or grammatical constructs could be so far out of our zone of proximal development (i + 5 in Krashen-speak) that it simply goes over our head, with very little that actually "sticks".

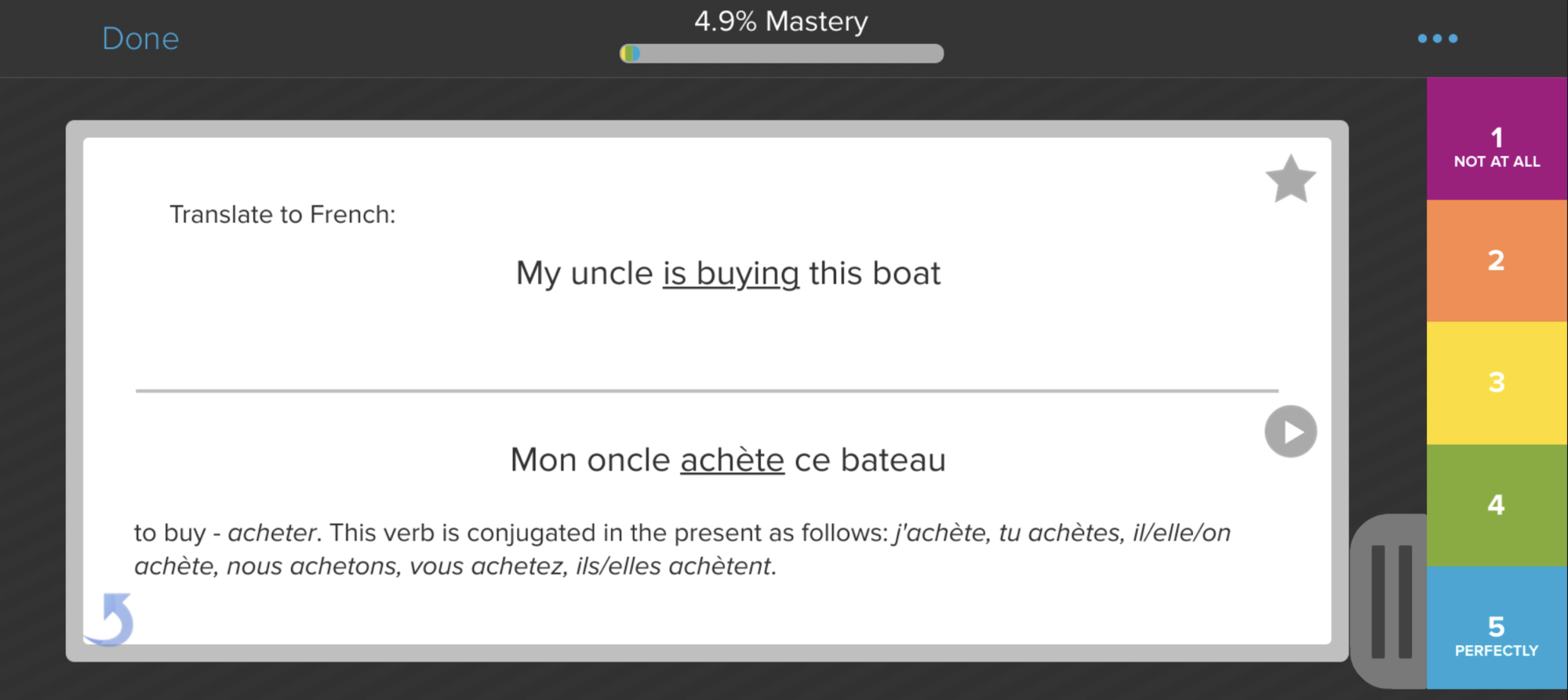

Brainscape's Lesson decks were laboriously developed to address exactly this inefficiency so that even new complete sentences never introduce more than one previously unseen learning objective at a time. It's always just i +1.

See the example below. The only new concept in the sentence is the conjugated verb "[he] is buying" (achète), which is underlined. All of the other concepts in the sentence (i.e. the possessive "my", the noun "uncle", the noun "boat", and the demonstrative pronoun "this") have presumably already been introduced in earlier cards, and have already been naturally repeating as Brainscape's spaced repetition system has progressed through the curriculum up to this point. The introduction of new concepts could hardly be more incremental than this!

The second noteworthy component of Brainscape's Sentence Builder decks is that the "answer" side of each flashcard adds a supplementary explanation of the new underlined concept, explaining any grammatical nuances or variants that the user should be aware of. (And any such variants are themselves still individually re-introduced in future cards.)

This is the opposite order of how grammatical concepts are taught in textbooks, which usually teach a lesson first and then give examples afterward. By introducing each concept through a spoken sentence and then providing the explanation, Brainscape again mimics the process of having a human tutor with you, who corrects you when you are initially unable to utter the phrase yourself, and then explains the concept in plain English.

White and many others show that native-language feedback can be instrumental in accelerating the internalization of complex grammatical rules. (See our more complete discussion of the role of the mother tongue in second language acquisition.

3.3.2. Vocab Enrichment decks

Staggered in between each of the Lesson decks in Brainscape's ICE language-learning curriculum are Vocab Enrichment decks, which help fill in the learner's level-appropriate gaps in vocabulary.

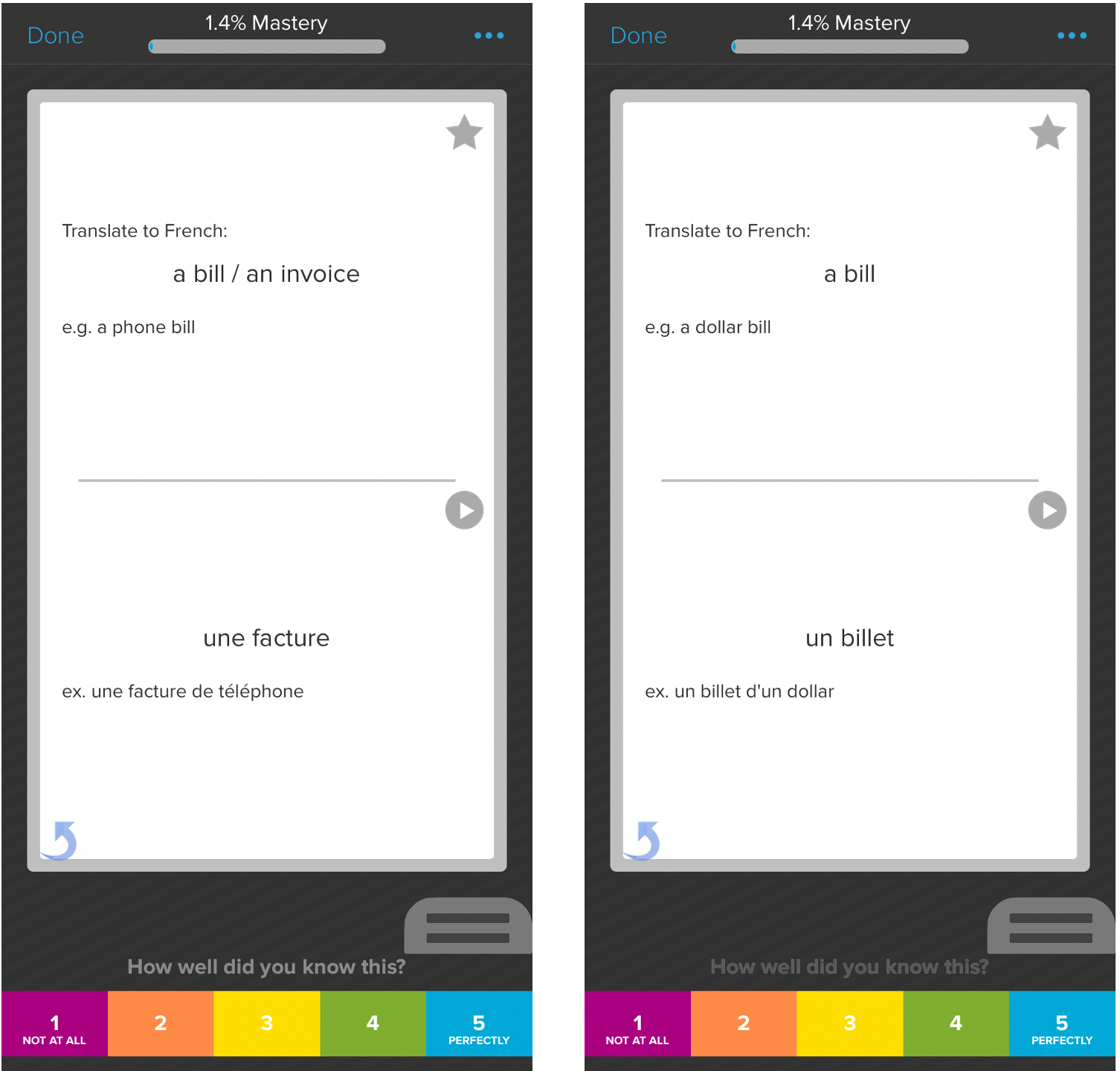

These decks are extremely different than the typical "vocab flashcards" that you might find on other apps or content marketplaces. The reason is that each Brainscape Vocab Enrichment flashcard contains not a word, but a semantic root with an unambiguous clarifier. In some cases, that semantic root could be just one meaning of a single word. In other cases, it could be multiple words that are synonyms of the exact same meaning.

For example, consider the English word "bill". A typical language app or vocab game would likely just present the word "bill" on the screen and expect that the user can translate it into the target language without additional context. But "bill" could mean different things! Brainscape instead breaks each major meaning into its own separate flashcard, paired with any relevant synonyms of that particular context, and a clarification or example phrase that makes it clear which semantic root is being referred to.

Brainscape's division of Vocab Enrichment exercises into their semantic roots ensures that you are not just "memorizing words," but rather that your brain is internalizing actual meaning that you will naturally be able to incorporate into your own sentences going forward.

The reasons that no other language app provides such exercises are that (i) most apps' vocab-practice interfaces are configured only for 1-word answers, which may be great for fun games and for tabulating leaderboards but is not as flexible as an open flashcard canvas; and (ii) the organization of an entire language's words into these semantic root pairings (and their respective clarifiers) is a tremendous undertaking that is not feasible via just a programmatic import of some existing foreign language dictionary.

Brainscape built the comprehensive database underlying our 20,000-word Vocab Enrichment series over the course of several years, with the work of over a dozen linguists who cross-checked semantic roots over several languages to ensure that they were universally extensible.

To learn more about the cumbersome process we undertook in creating this valuable asset, check out our separate article: Getting to the semantic root in language-learning software.

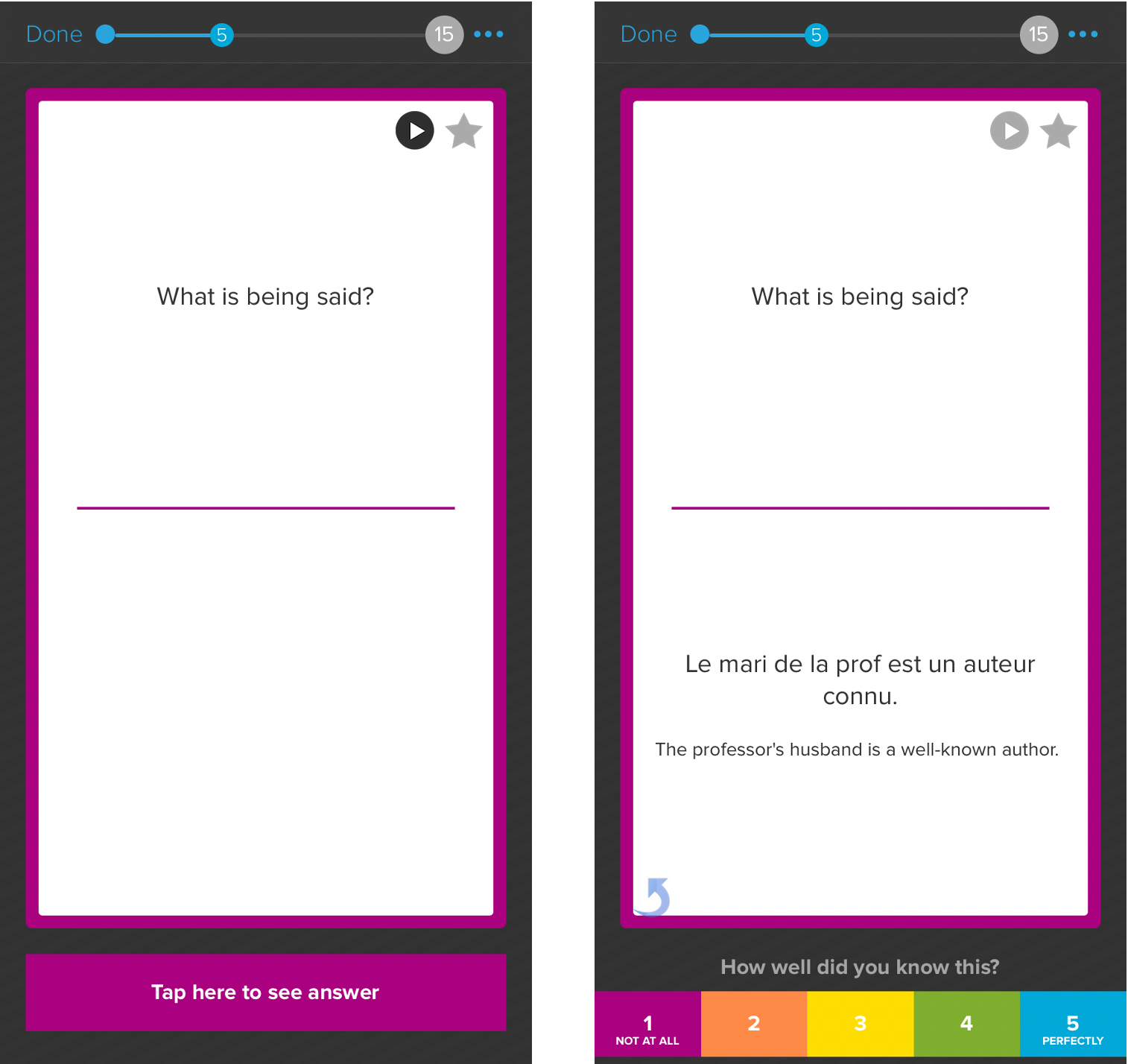

3.3.3. Listening practice decks

The final deck type in Brainscape's ICE language-learning curriculum is the Listening Practice deck. Each of the four major levels in Brainscape Spanish and Brainscape French conclude with this type of deck, in order to reinforce the words and concepts from that level without the benefit of initially seeing any words on the screen.

On the front side of each flashcard in these Listening Practice decks, the user listens to a phrase spoken by a native speaker at a natural (relatively quick) pace. The user tries to formulate the sentence in her head before manually revealing the correct answer when she is ready. And then, just as on other Brainscape flashcards, the user is asked to rate her confidence level for how accurately she was able to parse that sentence from the audio she had heard in the initial pronunciation.

The ability to pick out the actual spoken words from a rapidly spoken stream of audio is an understandably critical exercise for any language learner. Yet only Brainscape's ICE curriculum makes these exercises so accessible, bite-sized, and amenable to ongoing spaced repetition henceforth.

In fact, Brainscape considers these listening exercises so important that we advise users that their understanding of the actual meaning of these sentences is secondary to their simply identifying the words that are spoken. Sure, the translated meaning is always included below the correct sentence in the target language, but all the sentence's respective words and grammatical concepts are already fully covered in their own separate dedicated flashcards elsewhere in the curriculum.

Altogether, the combination of Brainscape's interwoven Sentence Builder, Vocab Enrichment, and Listening Practice decks, studied progressively, presents an optimal stream of atomic and incrementally introduced language concepts that have never before been so accessible in a spaced repetition language learning system.

3.4. Adaptability to your own experiences

The final unique advantage of Brainscape's combined ICE curriculum and software is the ease with which a user can find or add flashcards for words that they encounter in their daily life. There are two mechanisms by which a Brainscape user can do this: (1) Search and assimilate or (2) Make a flashcard.

3.4.1. Search and assimilate

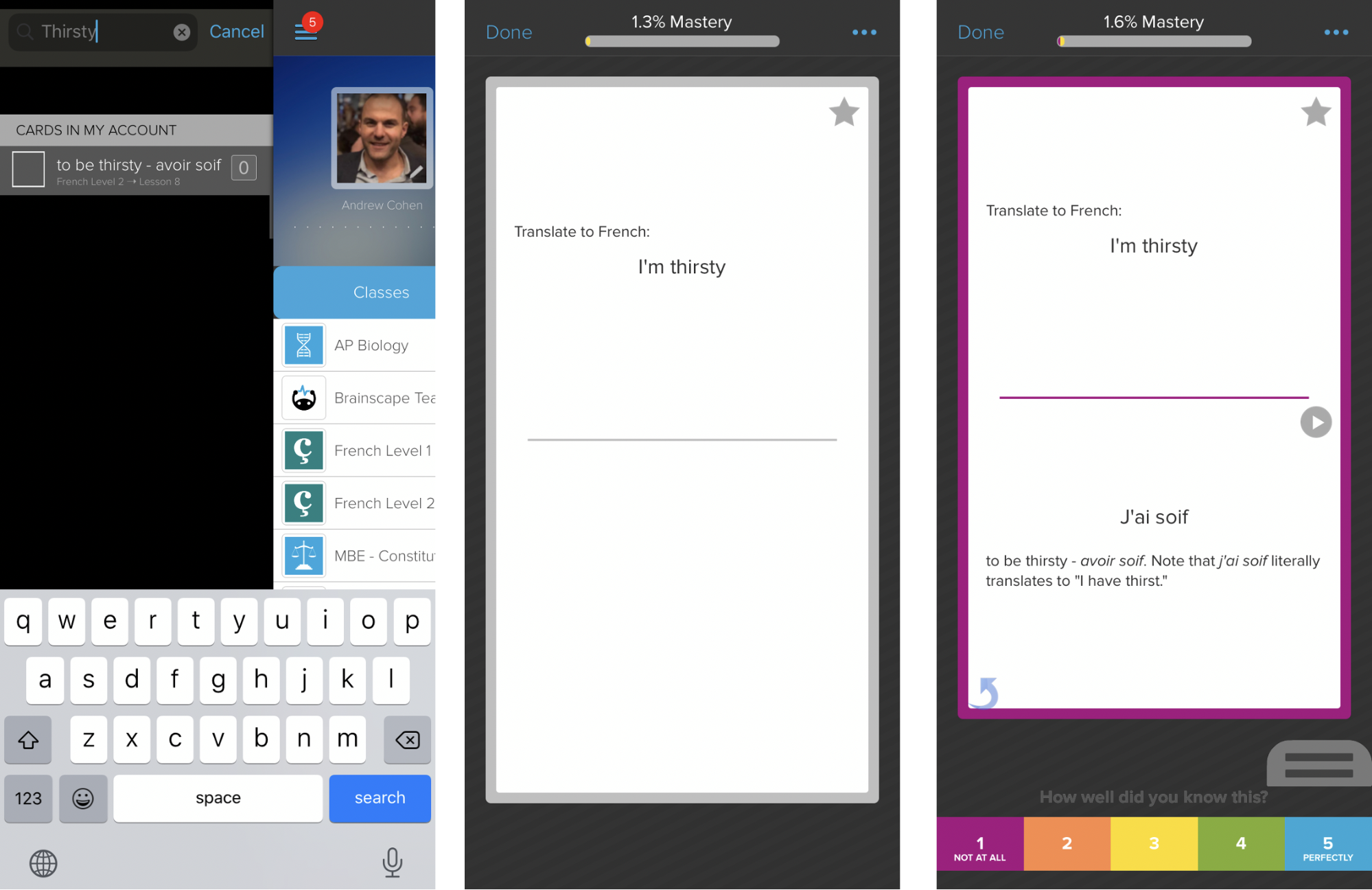

Let's say you're a beginner French learner on the streets of Paris and you want to tell your new companion that you are thirsty. Sure, you could look up the word "thirsty" in your handy French dictionary app. But you are quite confident that Brainscape must include that common word in its Learn French curriculum. You just haven't gotten to it yet.

So you decide to look up "thirsty" in the Brainscape app's handy Search feature, and voilá—there's the card for "to be thirsty" (avoir soif). It happens to be in Lesson 8, but you are currently only up to Lesson 3 yourself.

So you open the flashcard from search results, you reveal the answer, and then—just as if you were studying the flashcard as part of your regular lesson progression—you rate your confidence on that flashcard. In this case, because the phrase is difficult for you, you decide to rate yourself a "1" (red—not confident).

The magic of this approach is that the card will now show up in your ongoing progressive studies! Even when you go back to studying in Lesson 3, this newly rated "thirsty" card will be included in Brainscape's spaced repetition algorithm (in addition to the previously seen cards from Lessons 1 and 2 and their respective Vocab Enrichment decks).

No other language app offers such a seamless ability to accelerate a more advanced concept into your stream of spaced repetition, as the result of your premature exposure to it in the real world. As research shows, you are magnitudes more likely to remember a concept when you can relate it back to a practical experience than if you had simply encountered it in the course of a standard language-learning curriculum.

3.4.2. Make a flashcard

In the event that you had searched for a word in Brainscape and do not find it in our existing curriculum, you can easily just create your own flashcard on the fly! This is a common case for local slang words that may not have been covered in Brainscape's more universal collection of concepts (but which you may have procured a translation from a friend or an alternative dictionary source).

To make a flashcard, simply choose which deck you want to add it to, type the question and answer, and BOOM—the card can now show up in your ongoing progressive study mixes in Brainscape. Our web app will even allow you to upload your own custom audio files to help you remember the pronunciation each time you repeat the flashcard going forward.

4. Your fastest path to foreign language fluency

In this article, we have shown that Brainscape's ICE program provides the ideal combination of curriculum + spaced repetition for the more rapid and convenient acquisition of any foreign language. No other software introduces and reviews concepts in a pattern that is as challenging, progressive, or highly engaging of adult learners’ most useful language acquisition faculties.

We encourage readers interested in additional products to keep an eye on Brainscape's foreign language flashcards page as we develop new premium products that build upon the tremendous feedback we've already received about our Spanish and French products.

And finally, we recommend that any language learner use flashcards—Brainscape or otherwise—as a component of a more holistic set of resources that includes real-life resources such as blogs, news, video clips, and human conversation partners. You can find dozens of such recommendations in our complete foreign language-learning toolkit.

Best of luck in your language journey!

Sources

Janiszewski, C., Noel, H., & Sawyer, A. G. (2003). A meta-analysis of the spacing effect in verbal learning: Implications for research on advertising repetition and consumer memory. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 138–149.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Krashen, S. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. Englewood, NJ: Laredo.

Russell, J., & Spada, N. (2006). The effectiveness of corrective feedback for the acquisition of L2 grammar. In Norris, J.D. & Ortega, L. (Eds.), Synthesizing Research on Language Learning And Teaching (pp. 133-164). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Schlichting, M. L., & Preston, A. R. (2014). Memory reactivation during rest supports upcoming learning of related content. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(44), 15845-15850.

Swain, M. (2005). The Output Hypothesis: Theory and Research. In Hinkel, E. (Ed.), Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 471-484). Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Toth, P.D. (2006). Processing instruction and a role for output in second language acquisition. Language Learning, 56(2), 319-385.

White, L. (1991). Adverb placement in second language acquisition: Some effects of positive and negative evidence in the classroom. Second Language Research, 7(2), 133-161.