If you are seriously attempting to learn a foreign language, someone has probably recommended that you watch movies, explore podcasts, or listen to music in that language in order to speed up your learning. These listening exercises are all consistent with the input hypothesis, which basically says that, if you listen to enough language, you'll eventually pick it up.

But can you learn a language by primarily listening? No! Sure, you may have learned your first language by mostly listening for your first 18 months of toddlerhood, but I think you might want to start making progress in your second language more quickly than that!

It turns out that if you are a beginner or intermediate learner, you will be much better served by actually practicing speaking that language, no matter how badly you speak it. The trick is to develop the right feedback loops to help you self-correct and align your new verbal concepts to the inputs you continue to hear and read.

Let's take a look at why speaking will help you learn a second language. And be sure to check out our complete toolkit for the best ways to learn a language online, where we recommend dozens of tools and resources, including places to find native speaking partners for free.

You can't learn a language by listening only

The output hypothesis

In contrast to the input hypothesis, Merrill Swain and others developed the comprehensible output hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that it is by speaking that learners can make the most headway on a language because conversation gives them an opportunity to assess their own knowledge as well as immediate feedback.

A natural way to self-assess

Contrary to claims made by popular “total immersion” programs that, the trick to learning a language is to use conversation or translation to help elicit words and phrases from your existing bank of knowledge (or just beyond it). This makes speaking a valuable language learning method—just as much as listening.

A live conversation is ideal, of course, as it will challenge you to produce intelligible sentences from scratch, while providing immediate feedback (and hopefully correction) from the native speaker.

But translation exercises can be almost as effective, as they force you to produce specific phrases in the target language. You just need to ensure that you get quick feedback when your translation is eventually corrected (either by an instructor, a native speaker, or a language software program). The right audio accompaniments to translation can also help you improve your pronunciation and give you a better chance of losing your accent and sounding more like a native.

Actively producing phrases or sentences in the target language is an effective learning exercise since it prompts learners to “recognize consciously some of their linguistic problems”. In other words, production, particularly when accompanied by corrective feedback, is useful because it allows you to better assess your own confidence in how well you know each concept, thereby facilitating optimal learning techniques such as confidence-based repetition.

Incremental feedback

There is a significant body of research supporting the idea that production helps improve metalinguistic analysis and mental refinement of grammatical structure. Izumi and colleagues further illustrate the extent to which production practice leads to improved performance on production-centered post-tests. Participants in their experiment were instructed to generate their own written response to a given prompt, followed by exposure to a model response written by a native speaker. Results suggested that the opportunity to produce one’s own response before exposure to the model leads to significantly greater post-test scores.

Izumi et al.’s finding is interesting given that participants were provided feedback in only one large chunk (i.e. exposure to the entire passage) rather than incremental corrective feedback for each sentence as it was written. Research by Corbett and Anderson suggest that the Izumi et al. experiment’s performance enhancements could have been even greater if the learners had been given more frequent feedback on their correctness. The idea of regular feedback has become a standard feature of most modern educational software and video games.

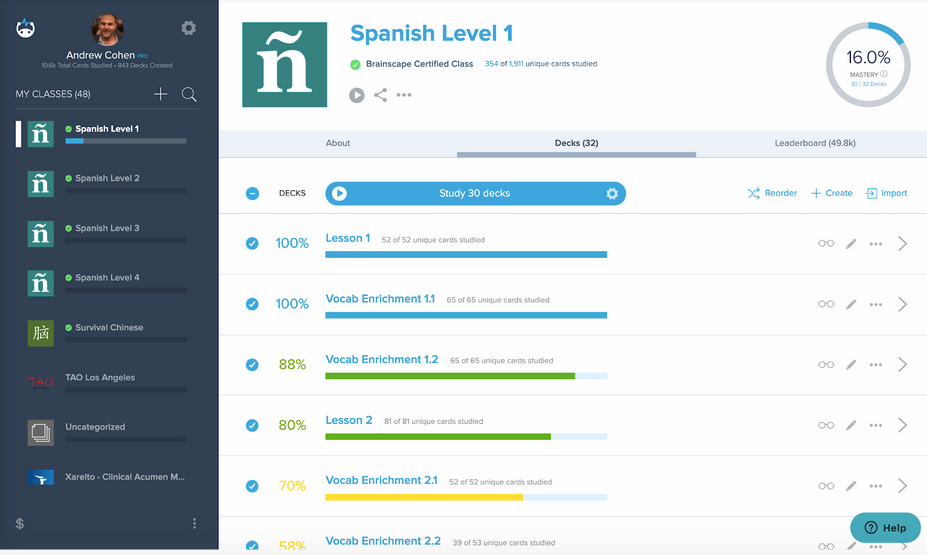

Use Brainscape to learn a new language efficiently

Brainscape is perhaps the most effective tool available to practice such production/feedback in a convenient, modular, mobile fashion. Its technique is rooted in scientifically proven language-learning principles like spaced repetition. Brainscape breaks down a language into bite-sized, understandable bits and teaches it incrementally, meaning one new concept at a time. This allows you to really learn the language, rather than just struggle through thousands of new words and concepts.

You can find foreign language flashcards on Brainscape's marketplace, and you can also add your own flashcards and study them from any device. Brainscape keeps all your progress in sync between web and mobile and gives you convenient study reminders to keep you on track.

[Brainscape has even created a toolkit recommending dozens of other key apps and websites to help you learn a foreign language on your own]

Although it does not require the user to manually type a translation for each cue, Brainscape's foreign language flashcards do essentially provide sentence-by-sentence feedback by revealing the correct sentence construction (and audio supplement) immediately after the learner has attempted to mentally generate it herself.

This is as closely as an autonomous technology can approximate the experience of conversing with that ideal native speaker who provides validation after every sentence uttered. Seeing/hearing immediate feedback, along with a grammatical explanation of the new concept, helps the Brainscape user provide a more accurate confidence assessment and therefore a more optimal interval of time before that concept is reviewed.

You can't learn a language by listening only.

Whatever tools you use for input and output practice, remember that you also need to speak. Conversing with a native speaker gives you the opportunity to read back into your mind for the right vocabulary and to get immediate feedback on your language. It also helps show you where your weaknesses are, so you can continue your studying journey as effectively as possible.

Read: Learning a new language when you're older and how to do it!

References

Corbett, A.T. & Anderson, J.R. (2001). Locus of feedback control in computer-based tutoring: Impact on learning rate, achievement, and attitudes. Proceedings of ACM CHI 2001 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 245-252. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/365024.365111

Izumi, S., Bigelow, M., Fujiwara, M., & Fearnow, S. (1999). Testing the output hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 421-452. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44486913

Russell, J., & Spada, N. (2006). The effectiveness of corrective feedback for the acquisition of L2 grammar. In Norris, J.D. & Ortega, L. (Eds.), Synthesizing Research on Language Learning And Teaching (pp. 133-164). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In Hinkel, E. (Ed.), Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 471-484). Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Toth, P.D. (2006). Processing instruction and a role for output in second language acquisition. Language Learning, 56(2), 319-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0023-8333.2006.00349.x

Image attribution for first image (closeup of microphone) Photo by Richard Clyborne of Music Strive.