Ear Flashcards

(30 cards)

What is the definition and epidemiology of acoustic neuroma?

Acoustic neuromas (also known as vestibular schwannomas) are benign tumours of the Schwann cells and primarily originate within the vestibular portion of cranial nerve VIII. ‘acoustic neuroma’ is, therefore, a double misnomer.

The median age is 50 years and occurs in 1 in 100,000. They account for 6% of all intracranial tumours.

What are the clinical features of acoustic neuromas?

Early symptoms with insidious onset: caused by pressure on the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) as a result of tumour expansion into the internal acoustic canal (internal auditory meatus).

- Cochlear nerve involvement can lead to unilateral sensorineural hearing loss (most common symptom) or tinnitus.

- Vestibular nerve involvement manifests as dizziness or unsteady gait and disequilibrium.

Late symptoms are caused by the pressure of adjacent structures within the cerebellopontine angle.

- Trigeminal nerve (CN V) involvement: Paraesthesia (numbness), hypoesthesia (decreased sensation), and/or unilateral facial pain

- Facial nerve (CN VII) involvement: Peripheral, unilateral facial weakness that can progress to paralysis

- Compression of the cerebellum can manifest as ataxia, and compression of the 4th ventricle can lead to hydrocephalus.

Describe the investigations/diagnostics of acoustic neuroma

Audiometry will show hearing loss with a greater deficit for higher frequencies. This is the best initial screening test as > 95% of patients will have some type of hearing loss.

Cranial nerve testing:

- Weber test: lateralisation to the normal ear

- Rinne test: air conduction > bone conduction in both ears

- Brainstem-evoked audiometry: delay in cochlear nerve conduction time on affected side finding. Less commonly used because of the increased sensitivity and availability of MRI screening.

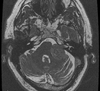

All patients with unilateral hearing loss are sent for a gadolinium-enhanced MRI. CT with and without contrast is an alternative for those who cannot undergo MRI.

- MRI shows an enhancing lesion by the internal auditory canal, with possible extension into the cerebellopontine angle. As well as the absence of dural trail.

How is an acoustic neuroma managed?

For those with large tumours, tumours that are growing on serial scans, or significant hearing loss, the main treatment options are surgery or focused radiation therapy. This is followed up by yearly scans.

Small tumours (<1.5cm) that are not bothersome can be observed by yearly scans.

What is the definition and epidemiology of BPPV

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo is a vestibular system disorder characterised by sudden, short-lived episodes of vertigo elicited by specific head movements. BPPV is the most common cause of vertigo, with a peak incidence between 50-70 years of age.

What is the aetiology and pathophysiology of BPPV

Around 50-70% are primary/idiopathic, and the rest are secondary to head trauma, labyrinthitis, vestibular neuritis, Meniere’s disease, migraines, ischaemic processes etc.

It is thought that canalithiasis plays a major role in the pathophysiology. In canalithiasis, free-floating endolymph particles called canaliths (which are possibly otoconia or calcium carbonate particles), originating from the otolith membrane in the utricle, migrate into the semi-circular canals over time via natural head movements.

What are the clinical features of BPPV

The patient experiences intense vertigo brought on suddenly by specific head movements (e.g. looking up or turning the head to the left). If vertigo is not precipitated by certain movements, then a central cause is considered.

The vertigo itself lasts for less than 30 seconds, while other conditions last for much longer. Associated symptoms of nausea, imbalance and light-headedness may persist for a longer duration. BPPV is episodic, with attacks occurring repeatedly for weeks or months.

On Examination

Patients have a normal neurological examination, apart from a positive Dix-Hallpike Manoeuvre (see video) which indicates BPPV. The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre involves holding the patient’s head upright at a 45o angle to one side, then lowering their head to below their trunk - a positive sign is indicated by nystagmus which may last for a minute.

How can BPPV be investigated?

A Dix-Hallpike Manoeuvre or supine lateral head turns can, along with the history, provide a diagnosis.

An audiogram will be normal in BPPV.

A brain MRI may show a central condition that mimics BPPV.

How is BPPV managed?

Reassure patient that the condition is very benign. Perform the Epley manoeuvre which can often cure the BPPV right away by pushing the stone out of the semi-circular canal.

What is the definition and epidemiology of Meniere’s disease?

Meniere’s disease/syndrome is an auditory disease characterised by sudden-onset of vertigo, low-frequency hearing loss, low-frequency roaring tinnitus, and sensation of fullness in the ear.

Affects around 15.3 in 100,000 with onset in the fourth decade.

What are the clinical features of Meniere’s disease?

It is caused by factors (largely unknown) that lead to an increase in endolymph in the canals. This causes symptoms of tinnitus and fullness and hearing loss.

Eventually, the Ressiner’s membrane ruptures, allowing endolymph to mix with the perilymph, producing symptoms of sudden-onset vertigo. Attacks can last from minutes to hours, and is usually associated with nausea and vomiting.

On Examination

Positive Romberg’s test and nystagmus during acute attacks.

What is the natural history of Meniere’s disease?

- Symptoms resolve in the majority of patients after 5-10 years

- The majority of patients will be left with a degree of hearing loss

- Psychological distress is common

What are the investigations for Meniere’s disease?

Pure-tone air and bone conduction studies show unilateral sensorineural hearing loss of low-frequencies. As disease progresses, middle and high frequencies are also affected.

Speech audiometry shows no discrepancies on speech recognition threshold.

Tympanometry shows normal tympanogram.

Describe the management of Meniere’s disease

- ENT assessment is required to confirm the diagnosis

- Patients should inform the DVLA. The current advice is to cease driving until satisfactory control of symptoms is achieved

Acute attacks: buccal or intramuscular prochlorperazine. Admission is sometimes required.

Prevention: Betahistine and vestibular rehabilitation exercises may be of benefit

What is the definition and epidemiology of Cholesteatoma?

Cholesteatoma is a non-cancerous growth of squamous epithelium that is ‘trapped’ within the skull base causing local destruction.

- It is most common in patients aged 10-20 years.

- Being born with a cleft palate increases the risk of cholesteatoma around 100 fold.

What are the potential complications of Cholesteatoma?

It is important to diagnose as they have a high risk of complications:

- The can extend posteriorly, causing conductive hearing loss (ossicles), vertigo (semicircular canals), or sensorineural hearing loss (cochlea).

- They can also extend superiorly, resulting in complications such as facial nerve palsy, meningitis, cerebellar abscess or venous sinus thrombosis.

What are the clinical features of Cholesteatoma?

- Foul-smelling, non-resolving discharge

- Patients may also have hearing conductive hearing loss

Other features are determined by local invasion:

- Vertigo

- Facial nerve palsy

- Cerebellopontine angle syndrome

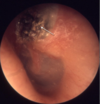

What area of the tympanic membrane is important to visualise if suspecting a cholestatoma?

The attic (pars flaccida) is extremely important to visualise, and any crusting or ear wax obscuring the attic is a cholesteatoma until proven otherwise.

What is acute otitis media, and what is it caused by?

Acute otitis media (AOM) is a viral or bacterial infection of the middle ear that is most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- 70% of children <2 years old experience AOM at least once.

Bacterial superinfection following a viral URT infection (95% of cases)

- S. pneumoniae (most common: 35% of cases)

- Haemophilus influenzae (25% of cases)

- Moraxella catarrhalis (15% of cases)

Obstruction of the eustachian tube during a URT infection causes accumulation of middle ear secretions. This allows bacterial superinfection. In infants, the eustachian tube is shorter, narrower and more horizontal making them more prone to developing AOM.

What are the clinical features and examination features of otitis media?

Clinical Features

Infants may have vague signs such as incessant crying and refusal to feel. A clue is the may be repeatedly touching the affected ear. They may also present with fever and febrile seizures.

Older children may also complain of throbbing earache and there may be hearing loss in the affected ear.

Patients may have a tender mastoid in late stages.

Diagnosis

Otoscopy may show bulging and erythematous tympanic membrane with loss of light reflex.

Describe the management of otitis media

Management is symptomatic pain relief with paracetamol and ibuprofen. Antibiotics are not always indicated.

A 5-day course of amoxicillin (or erythromycin) should be prescribed immediately if:

- Symptoms lasting more than 4 days or not improving

- Systemically unwell but not requiring admission

- Immunocompromise or high risk of complications secondary to significant heart, lung, kidney, liver, or neuromuscular disease

- Younger than 2 years with bilateral otitis media

- Otitis media with perforation and/or discharge in the canal

What are the potential complications of otitis media?

What is glue ear?

Recurrent ear infections can lead to otitis media with effusion (OME) (also called glue ear) which the most common cause of conductive hearing loss. This is relatively common in children aged 2-7 years, and resolves spontaneously.

What are the risk factors for otitis media with effusion?

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is more common in children with the following:

- Cleft palate (causing impaired function of the eustachian tube).

- Down’s syndrome (impaired immunity and mucosal abnormality increasing susceptibility to infection).

- Primary ciliary dyskinesia.

- Allergic rhinitis.