The science of learning is the study of how the brain absorbs and understands new information and then stores it away for use whenever needed.

Why is this important?

Well, understanding the science behind learning equips anyone with a brain with an instruction manual that says: "Here's how to feed your brain information in a way that will optimize its understanding and retention."

Understanding this helps you to constantly improve the efficiency with which you attack new learning challenges, bridge your knowledge gaps, and retain new information!

It'll also make you a much better teacher, whether you're delivering a lecture to a study hall full of law students or showing your kid how to chop carrots.

Have I piqued your curiosity? Good!

In this article, I'll be sharing with you some of the most significant breakthroughs humans have made in the science of learning to give you tips on how to optimize your brain for learning while minimizing mental inertia and burnout!

8 Critical Discoveries About the Science of Learning

Even after all of humankind's breakthroughs in the science of learning, we still don't have a thorough read on this pink noodle of an organ.

That said, we do have a much better understanding of how we learn, organize, remember, and retrieve information. So let's explore what we've discovered about how students learn so that you can engineer the most efficient and effective study program for yourself, your kids, or your students...

More Information Doesn’t Mean More Learning: Breakthrough in Understanding How We Learn # 1

Processing information takes resources. That means that the brain has to do work to understand. This is the reason you can't simply cram more information into your noggin and expect a corresponding linear increase in learning.

Cognitive scientists refer to the point at which a person's brain becomes overwhelmed by new information as "cognitive overload". Too much new information results in cognitive overload, and this ultimately reduces learning.

How can you reduce cognitive overload? Two ways:

- The quantitative method: Provide less NEW information. You make sure that you or your students understand most of what they've learned before presenting new information.

- The qualitative method: Change the way you present new information so that it is less overwhelming.

One way to automate the intentional, systematic delivery of information to your brain in a way that avoids cognitive overload is to use a flashcard app like Brainscape, which uses confidence-based spaced repetition.

Here's what that means. Every flashcard asks you to rate—on a scale of 1 to 5—how well you knew the concept it presented. If you knew it really well, you'd rate it a "5". If, however, you didn't know the answer at all, you'd rate it a "1".

Depending on your rating, Brainscape's algorithm will repeat the concepts you struggled with more often while saving you time reviewing the concepts you do know very well. Moreover, the algorithm will ensure that you don't see any new flashcards until there is a relatively low amount of 1s in the cards you've already rated.

This ensures that you don't get too much new information before you've got a good grasp of the information you've already seen. Cognitive load doesn't get too high, you never get overwhelmed ... bing bang boom, you're learning in peace!

Emotions Influence the Ability to Learn: Breakthrough in Understanding How We Learn # 2

Our emotions affect most aspects of our lives, from our perception of information to our ability to remember it and solve problems. This is especially true for children, who are less able to regulate their emotions.

Consequently, feeling anxious, stressed, ashamed, or fearful has a dramatic and deleterious effect on learning. These emotions activate the limbic system, which interferes with memory generation.

This is why it's so important to develop trust with children and create safe learning environments: not only to help them feel more comfortable but also to help them learn better.

Mistakes Are an Essential Part of Learning: Breakthrough in the Science of Learning # 3

No one aims for failure. It's something we generally want to avoid. But the science of learning shows that making mistakes is essential for learning.

We don't all learn to ride a bike the very first time we get on it—we get better with practice. It's the same with any learning curve, whether it's academic or skills-based: making mistakes is essential to the learning process.

Moreover, the pressure to succeed may inhibit learning. Research finds that students learn and perform better when they are told that failure is a normal and expected part of learning. Naturally, feeling less pressure leads to bolder, more confident decision-making, which often leads to better performance. It also helps us absorb the lessons in failure rather than allowing shame to take center stage.

The Brain Needs Novelty: Breakthrough in the Science of Learning # 4

Another huge breakthrough in the science behind learning is that boredom kills your attention and willpower to learn.

Unfortunately, boredom is unavoidable when you consider the amount of repetition it takes to master any subject or skill.

(In college, I was deeply fascinated by severe weather phenomena, but even I had to learn a ton of boring physics and math to be able to understand the mechanics of how hurricanes are formed over the world's equatorial regions.)

According to the science of learning, the brain craves novelty. Novelty releases dopamine, which is a neurochemical that's part of the pleasure center of our brains. We find it intensely rewarding. Dopamine plays a huge role in motivation for learning.

The takeaway here is to present information to yourself or your students in interesting, novel ways. For example, many teachers reinforce their material with Brainscape's digital flashcards. Through sound, images, and unexpected orders, Brainscape provides a novel way to present the same information.

Learning Styles Do Not Matter as Much as We Thought: Breakthrough in Understanding How We Learn # 5

For decades, we've held onto the idea that—like horoscopes—everyone has a different learning style: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc. But, again, like horoscopes, this belief doesn't align with the actual science of learning. The brain, with few exceptions, is designed to learn optimally the same way.

What differs from person to person are our preferences for learning. Some people prefer reading over listening to lectures, some prefer watching videos to listening, and others prefer working with their hands to all of the above. But across the board, there's little evidence that any of these preferences lead to better learning. Learning styles just may not work.

That doesn't mean that all learning activities are created equally.

For example, active recall is much more effective than re-reading, highlighting, concept mapping, or recognition of the right answer in later recall. Similarly, spacing learning out is better for recall than cramming. (But you probably already knew that, right?)

This is precisely why Brainscape is designed the way it is. It uses active recall, together with spaced repetition, to maximize learning.

The takeaway here is that the way we teach matters, based on cognitive science, not myths like learning styles. Instead, build active recall into your learning and space it out over time.

Brains Operate on the “Use It or Lose It” Principle: Breakthrough in How Students Learn # 6

As we learn, the brain is constantly building and re-building neural pathways. The pathways that are used the most get stronger, while those that aren't fade away.

This is the reason your French gets rusty when you don't use it, or why it'll take you a while to work out an algebra problem if you haven't done one in a while. With the brain, that old saying is true: if you don't use it, you lose it.

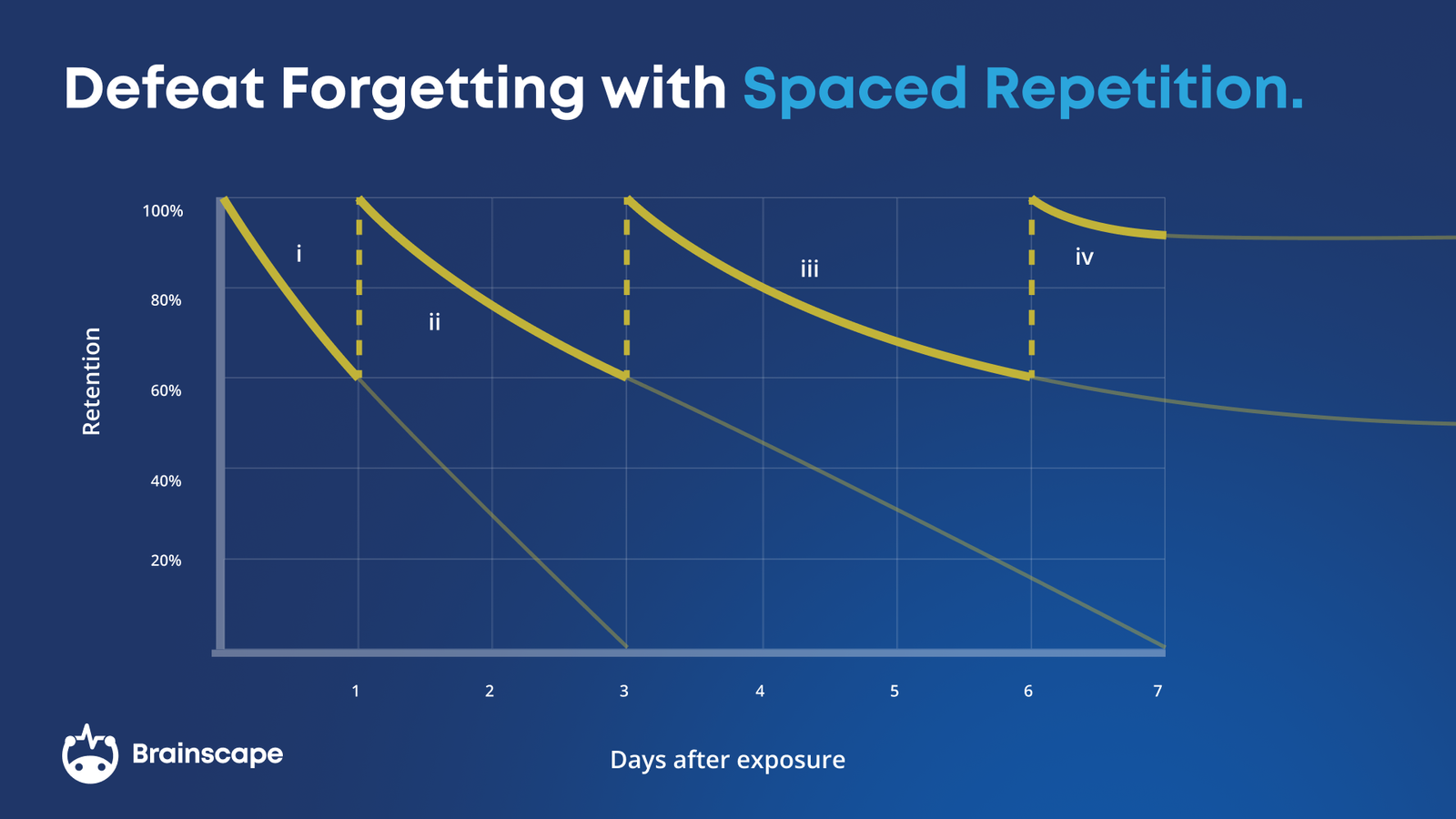

What this highlights is the importance of spaced repetition...

One of the most important breakthroughs in the science of learning is spaced repetition, which involves spreading out your learning so that you repeat a concept right at the point you otherwise would have forgotten it. This cognitive science learning strategy is proven to be the most powerful and efficient way to learn and remember information, which is why its integration into Brainscape's study algorithm helps you to learn twice as fast.

Learning is Social: Breakthrough in the Science of Learning # 7

However, the majority of people learn best through social interaction.

Collaborating with peers generally leads to much better learning outcomes. This is reflected in brain imaging studies as well: when information is presented by other people in a multi-sensory way, neuroimages show several neural networks functioning together at the same time. We learn information very effectively through social cues like recalling the words of others or emulating their actions.

The takeaway message here is to create opportunities for collaboration. This includes group work or peer teaching strategies. It can even be getting your class to work together to create flashcards.

Learning Happens Best Through Teaching: Breakthrough in the Science of Learning # 8

If you're a teacher, you'll be familiar with this: you never understand something as well as after having taught it. The science supports it: teaching others is one of the most effective study methods.

In fact, it has a name: the Feynman Technique: the most powerful way to deeply learn new information is to write or speak about that subject in simple terms, as though you're teaching it to a sixth-grader.

Trying to explain a subject simply yet eloquently consolidates what you already know while identifying any gaps you might have in your knowledge.

The takeaway: create opportunities for peer-teaching because explaining something reinforces knowledge. Get your students to teach new information to each other. Or even to their pet dog, plant, or rock.

FAQ: Breakthroughs in the Science of Learning

What is the biggest breakthrough in learning science?

Arguably, the biggest breakthrough is the discovery of spaced repetition: the idea that we retain information better when we review it at specific intervals over time. It’s backed by decades of research and underpins many of today’s most effective study tools, including adaptive flashcards.

What is the Science of Learning?

The science of learning is an interdisciplinary field that explores how people acquire, process, and retain information. It draws from neuroscience, psychology, and education to inform teaching methods and improve learning outcomes through evidence-based strategies.

What are two things scientists know about learning?

First, active recall is far more effective than passive review. Second, emotions significantly affect learning. Students learn better in safe, supportive environments where stress is minimized and curiosity is encouraged.

A Final Word on Understanding How Students Learn

Understanding how we learn is one of the most important things you can do to ensure that your learning (and teaching) is efficient and effective. It focuses your work on activities that actually enhance learning.

Because it's built on cognitive science research, Brainscape is a particularly effective tool for learning!

Additional Reading

- The Complete Cognitive Science Behind Brainscape

- The science of never forgetting: Spaced repetition for fast learning that lasts

- How brain science can help you learn a language faster

Sources

Autin, F. & Croizet, J. C. (2012). Improving working memory efficiency by reframing metacognitive interpretation of task difficulty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(4), 610. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0027478

Cohen, P. A., Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C. L. C. (1982). Educational outcomes of tutoring: A meta-analysis of findings. American Educational Research Journal, 19(2), 237-248. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00028312019002237

Fiorella, L. & Mayer, R. E. (2013). The relative benefits of learning by teaching and teaching expectancy. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(4), 281-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.06.001

Karpicke, J. D. & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772-775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Karpicke, J. D. & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966-968. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152408

Kirkland, M. R. & Saunders, M. A. P. (1991). Maximizing student performance in summary writing: Managing cognitive load. Tesol Quarterly, 25(1), 105-121. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587030

Li, P. & Jeong, H. (2020). The social brain of language: Grounding second language learning in social interaction. NPJ Science of Learning, 5(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0068-7

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105-119. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1454. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2017.01454

Wood, D. & O'Malley, C. (1996). Collaborative learning between peers: An overview. Educational Psychology in Practice, 11(4), 4-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266736960110402